NOVEMBER 26, 2018. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

Although grapevines have the potential to live for many decades, most vineyards have a productive lifetime limited by pests, diseases, and other factors. When farming costs regularly exceed grape revenues due to decreasing productivity, it is time to replant. Replanting is, of course, an involved and expensive endeavor, but it is also an opportunity for vineyard improvements that result in greater fruit production, enhanced berry quality, improved operational efficiency, and increased profitability. This article presents a systematic replanting process that considers those opportunities.

Evaluation of the Existing Vineyard

Begin the replanting process with a thorough examination of variations within the existing vineyard and the factors that contributed to its decline. Such an examination provides information essential for favorable vineyard redevelopment.

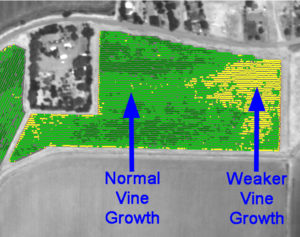

Delineate areas of weaker growing vines. Aerial photos or images are useful for this purpose, but often are not required because those who farm vineyards usually know the locations and extent of areas of restricted growth (Fig. 1). Even so, determining the perimeters of weak growth areas with global positioning system (GPS) coordinates is prudent because it facilitates targeted applications of resources prior to replanting, as well as efficient monitoring of vine growth and fruit production in the new vineyard.

Fig. 1. An aerial image showing areas of normal and weaker grapevine growth within a vineyard.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

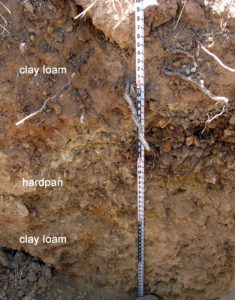

Fig. 2. Root zone profile of a recently removed vineyard in the Borden Ranch AVA.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

Record visual observations of weak growing vines, including comments regarding shoot length, internode length, leaf size, and foliage color. Note symptoms that suggest disease and mineral nutrient problems. Make trenches with a backhoe in both areas of weak and strong vine growth, and examine soil profiles for impervious layers (hardpan, claypan) and well-defined boundaries between layers that may limit downward water movement (Fig. 2). At the same time, note the extent, density, and health of roots. Collect soil samples from the walls of the trench for assay of soil-borne pests (nematodes, Phylloxera) and analysis of soil characteristics, including measures of texture and fertility.

Vineyard Removal

The next step of replanting is vineyard removal. Sanitation is a primary objective during this process. Even if there is no evidence of soil borne pests or diseases, there is a community of microorganisms residing in the soil capable of inhibiting the growth of new grapevines. They are adapted to the current rootstock and the environment immediately surrounding its roots.

Therefore, it is important to remove as many old roots as feasible. Effective root removal involves multiple passes, typically after vineyard removal, deep cultivation, and disking down ripper marks. It is also important to burn all excavated old vines and roots to eliminate them as sources of inoculum (Fig. 3). If feasible, a fallow period or the growing of a winter cover crop composed of multiple plant species will further diminish numbers of potentially harmful soil inhabitants.

Fig. 3. A vineyard burn pile.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

Ground Preparation

The third step of replanting is ground preparation for the new vineyard. Preplant is a prime opportunity to broadcast apply soil amendments across the entire vineyard land surface for large-scale changes in soil conditions. It is also an opportunity to greatly improve soil conditions within weaker growing areas of the former vineyard with liberal amendment applications. With your GPS determined perimeter, you are equipped to differentially apply them according to need.

Certain mineral amendments effect pH changes, such as lime or dolomite (increasing pH) and soil sulfur plus an organic amendment (decreasing pH). Gypsum, another mineral soil amendment, improves the balance between soil cations (calcium, magnesium, and sodium) and, in the process, improves soil structure (aggregate formation) and tilth. Almost all California soils benefit from preplant manure or compost, which increase soil organic matter, tilth, air and water penetration, and soil microbial activity and mineral nutrient availability. Making ground preparations during the autumn before planting allows the use of a winter cover crop as a cost effective alternative source of organic matter.

After amendment applications, deep cultivate the soil to facilitate air and water movement into and through the root zone of the new vineyard. In many replant situations; shallow ripping to depth of about 3 feet is sufficient to shatter compacted surface soil, thereby creating a uniformly permeable root zone across the vineyard site (Fig. 4). Other replant soils, if not properly prepared before the prior vineyard, may require deeper ripping or slip plowing to permanently disrupt and mix a claypan or a distinct interface boundary between subsoil layers. In all cases, ripping in two directions, one in the direction of the vine row and the other at a forty-five degree angle to the vine row, results in maximum soil shatter and the greatest return on investment.

Fig. 4. Recently ripped compacted soil near Lodi.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

Design the New Vineyard

Step four in the replanting process is vineyard design. Begin by selecting the variety (i.e. scion). The inherent vigor of the variety, potential soil borne pests, and soil conditions are factors to consider while selecting the rootstock. Always use a rootstock with a different parentage than the rootstock in the previous vineyard, which soil microbes are adapted to. In addition, use CDFA certified nursery stock for both the scion and rootstock to avoid debilitating virus diseases.

The anticipated vigor of the variety-rootstock combination will help you decide how to train and space the vines within the vine row. The in-row vine spacing and foliage growth habit of the variety are guides for trellis selection. Varieties with willowy or drooping shoots, such as Petite Sirah and Merlot, require foliage support while those with upright shoots do not. Space vine rows as close as the canopy growth characteristics of the variety will allow without severe hedging.

Vineyard Installation and Development

The final step of replanting is vineyard installation and development (Fig. 5). High quality materials and competent installation lead to low maintenance, durable replant vineyards. Following installation, carefully manage and train young vines to create well-formed, productive mature vines and a uniform, efficient replant vineyard.

Fig. 5. Newly installed vineyard in berms near Clarksburg.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

In Conclusion

Replanting involves all of the five steps given above. Remember, you only have one chance to do it right. So, take your time and pay attention to the details during replanting to ensure a successful new vineyard.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services October 2005 Newsletter, and was revised for this blog post.

Further Reading

Chaney, DE; Drinkwater, LE; Pettygrove, GS. Organic soil amendments and fertilizers. UC Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program, University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 21505. 1992.

Deep cultivation. UC Cooperative Extension.

Grant, S. Vineyard longevity. Progressive Viticulture. (www.progressivevit.com). March 26, 2015.

Grant, S. Evaluating vineyard soils in trenches. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (www.lodigrowers.com). February 17, 2016.

Grant, S. The economics of vineyard design: trellising, vine spacing, and row spacing. January/February 2000. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 20(5): 48-63.

Grant, S. Vineyard design and management for maximum efficiency. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (www.lodigrowers.com). February 22, 2018.

Grant, S. Selection a rootstock for a wine grape vineyard. Grant, S. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (www.lodigrowers.com). October 07, 2016.

Kaspar, TC: Singer, JW. The use of cover crops to management soil. In: Soil management: building a stable base for agriculture. Hatfield, JL; Sauer, TJ (Eds.). Agronomy Society of America and Soil Science Society of America, Madison, Wisconsin. 2011.

Ohmart, CP, Storm, CP, Matthiasson, SK (Eds.). Lodi Winegrower’s Workbook, 2nd Ed. Lodi Winegrape Commission. 2008.

Pearson, RW; Adams, F (Eds.). Soil acidity and liming. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, Wisconsin. 1967.

Verdegaal, PS; Sumner DA; Murdock, J. Sample costs for winegrapes: to establish a vineyard and produce winegrapes – Cabernet Sauvignon variety. San Joaquin Valley North – San Joaquin and Sacramento Counties, Crush District 11. Agricultural Issues Center, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Cooperative Extension. 2016.

Wildman, WE; Meyer, JL; Neja, RA. Managing and modifying problems soils. University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences Leaflet 2791. 1982.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.