JUNE 3, 2019. BY STAN GRANT.

The climate of most of California is well suited to grape growing, with consistent warm, dry weather and ample sunlight hours during most of the growing season. In addition, many California soils have the capacity to capture, store, and supply relatively large amounts of water from winter rains to grapevines, satisfying their early season needs. These natural assets combine to make excellent conditions for growing winegrapes. In fact, in some places conditions are so good that it is difficult to control the vigor of grapevine shoot growth and the extent of canopy development.

Vine Growth Vigor Control Options

There are only a few options for controlling grapevine growth capacity and its partitioning into shoot growth vigor and canopy development. Some rootstocks are reputed to limit the vigor of shoot growth and canopy size, but in field trials on deep soils in warm climates the influences of most common rootstocks are small to negligible. Similarly, deep-rooted cover crops, which compete with vines for soil resources, can slow shoot growth, but often insufficiently to achieve optimum canopy characteristics.

The most consistent method for controlling growth vigor is to dilute it into a greater numbers of buds through less severe pruning, either as more spurs or longer spurs. However, for vineyards with conventional designs, such as a T Trellis, less severe pruning usually results in high shoot densities (≥ 9 per foot cordon) and congested foliage in the fruit zone (Fig. 1). These canopy conditions are detrimental to fruit quality and fungal disease control.

Separating shoots and positioning some of them outward or downward effectively lessens shoot and canopy densities, but outward and downward positioned shoots grow and develop more slowly than upward shoots and the fruit they bear ripens later (May 6th, 2019 LWC Viticulture Coffee Shop Blog post). Such induced variability complicates vineyard operations, including harvest scheduling.

Removing alternate vines in the row and extending cordons on the remaining vines simultaneously adds spurs, moderates shoot densities, and devigorates shoot growth. Better still, instead of longer cordons, configure vines with more cordons while developing vineyards. In fact, quadrilateral cordon training on horizontally divided trellises is the most consistently successful method of diluting vine vigor (Fig. 2). Its success is evident in the number of quadrilateral cordon trained vineyards in California, which have steadily increased since they were introduced in the mid 1980’s. Horizontal canopy division also increases the amount of exposed leaf area and fruit yield per unit land, thereby increasing production efficiency (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Horizontally divided Cabernet Sauvignon vines on a non-positioned GDC trellis early in the growing season. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Fig. 3. Syrah vines with complete canopies during ripening on a Wye trellis, Lodi AVA. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Two Types of Horizontally Divided Trellises Common in California

Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon blanc, with their high growth capacity, stiff and upright shoots, and lobed leaves, are well suited to horizontally divided trellises without foliage support. When pruned to 1-bud spurs and with spurs positioned three to five inches apart, shoots of these varieties slightly spread, allowing diffuse and intermittent sunlight to penetrate fruit zones without leaf removal (Fig.4). Such horizontally divided trellises are sometimes called non-positioned GDC (Geneva Double Curtain) trellises.

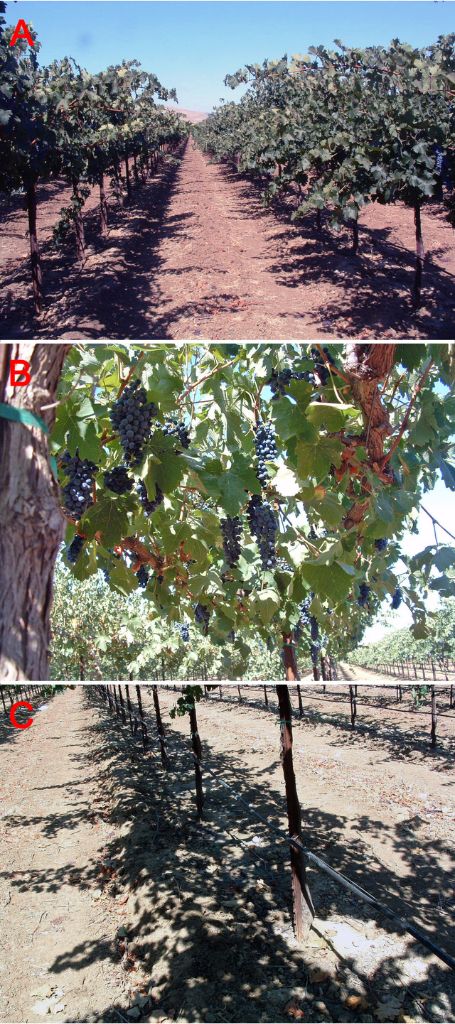

Fig. 4. Cabernet Sauvignon vines on a non-positioned GDC trellis (A) at ground level, (B) from below the fruit zone, and (C) the canopy shadow revealing light penetration; Salado Creek AVA, Patterson, California. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Varieties with draping shoots are also suitable for horizontal canopy division and quadrilateral cordon training, but foliage support is needed to minimize fruit exposure to direct sunlight (Fig. 5). For varieties including Chardonnay, Petite Sirah, and many others, the Wye trellis is the most cost-effective option for horizontal canopy division. It typically consists of a 24-inch cordon crossarm with a 42-inch foliage crossarm positioned about 14-15 inches above. The 18-inch difference in length between the crossarms, with 9 inches per side, is essential for catching draping shoots and exposing a majority of the leaves they bear to sunlight. In this configuration, vines may be mechanically pre-pruned (Fig. 6).

Elements of Horizontally Divided Trellis Design

Vine spacing, which affects the length of cordon per vine, is a critical variable in the design of vineyards with horizontally divided trellises. The inherent growth and fruit bearing capacity of the variety, and to a lesser extent, the influence of rootstock on vine growth, are determining factors. On deep soils, lower vigor varieties like Pinot noir are frequently spaced 4 feet apart in the row (8 feet of cordon/vine), moderate vigor varieties like Zinfandel are spaced 5 feet apart in the row (10 feet of cordon/vine), and higher vigor varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon are spaced 6 feet apart in the row (12 feet of cordon/vine). Such spacings facilitate balanced fruit and foliage growth with minimum inputs.

Cordons in vineyards with horizontally divided trellising systems are comparatively high, normally between 56-60 inches above the soil surface (Fig. 7). The long trunks, in combination with the expanse of cordons, create large woody frames that have large capacities for nutrient storage. Such capacities enhance vine resiliency to stresses and fruit ripening potential. In practice, yields of ripe fruit on horizontally divided trellises commonly range between 6-14 tons per acre or more, depending on production goals and thinning practices.

Fig. 7. Cordon height (≈ 60 inches) of Pinot gris on a Wye trellis, Grand Island.

(Progressive Viticulture©)

In addition to quadrilateral cordons, vines on horizontally divided trellises may be trained into interlocking “S” or “U” configurations. These forms are quicker to train because they require only a single cut at the top of the trunk, while quadrilateral cordons require additional cuts at each of the cordon wires. Fully trained “U” and interlocking “S” configurations also have back to back rather than opposing cordons on adjacent vines, with negligible gaps between them. As such, they have slightly longer cordons and more spurs than quadrilateral cordons.

Managing Horizontally Divided Trellises

As discussed above, horizontally divided vineyards differ from single canopy vineyards in significant ways. It follows their management would also differ. With a greater number of emerging shoots and leaves per unit land, horizontally divided vines deplete soil moisture stored from winter rains more rapidly than single canopy vines. Consequently, they require irrigation earlier in the growing season.

Further, because canopies of horizontally divided vineyards bear more exposed, transpiring leaves per unit land than single canopy vineyards, they require more frequent irrigation. Nevertheless, horizontally divided vineyards typically produce more fruit per unit water than single canopy vineyards and as a result, they have greater water use efficiencies. The macronutrient (e.g. Nitrogen) requirements of horizontally divided vineyards are similarly greater than those of single canopy vineyards.

Shoots on horizontally divided trellises extend and drape into the tractor row. Actually, this trait contributes to the relatively large leaf area per unit land and high production efficiency of horizontally divided trellises (Fig. 3). Accordingly, it is important to conserve as many leaves as possible through the growing season in horizontally divided vineyards. This means that hedging, should it become necessary for vineyard access, ought occur as late as possible and remove as few leaves as possible (Jun 06, 2017 Lodi Growers posting). Commonly, hedging of canopies on horizontally divided trellises consists of a combination of horizontal skirting cuts 15 to 18 inches above the soil surface and vertical cuts the width of the tractor hood. Excessive hedging, resulting in fewer than 12 leaves per shoot, delays ripening.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services May 2003 newsletter and was updated for the blog post.

Further Reading

Dokoozlian, N. Integrated canopy management: a twenty year evolution in California. In Dokoozlian, N; Wolpert, J (ed.), Recent advances in canopy management. Davis, California. July 16, 2009.

Freeman, BM; Tassie, E; Rebbechi, MD. Training and trellising. p. 42-65. In Coombe, B; Dry, PR (ed.) Viticulture: Volume 2 Practices. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1992.

Mollah, M. Practical aspects of grapevine trellising. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1997.

Smart, R. and M. Robinson. Sunlight into wine: A Handbook for Winegrape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1991.

Smart, RE. Canopy management. p. 85-103. In Coombe, B; Dry, PR (ed.) Viticulture: Volume 2 Practices. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1992.

Weaver, R. J. and A. N. Kasimatis. 1975. Effect of trellis height on with and without crossarms on yield of Thompson Seedless grapes. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 100, 252-253.

Weaver, R. J., A. N. Kasimatis, J. O. Johnson, and N. Vilas. 1984. Effect of trellis height and crossarm width and angle on yield of Thompson Seedless grapes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 35, 94-96.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.