MONDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2021. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

In winegrape vineyards, variety is among the most important factors affecting economic success. And, after all the time and effort we dedicate to selecting a clone, rootstock, and spacing-training-trellising-pruning system to optimize the performance of a scion variety, we are loath to change it. Sometimes, however, due to market circumstances beyond our control, changing varieties may be the best or only option for a vineyard to remain profitable.

Considering the Options

We have two options for changing varieties: replacing the entire vineyard or grafting a new scion onto the existing vines. Vineyard replacement is more expensive than field grafting due to the materials, labor, and time required to reach full production. Still, there are often compelling reasons to replace an entire vineyard. These include vines near the end of their productive lives, a rootstock or vineyard design poorly matched to the site or production objectives for the new variety, vineyard hardware near the end of its useful life, virus infection, and wood disease that has progressed deep into the trunks of a majority of the existing vines.

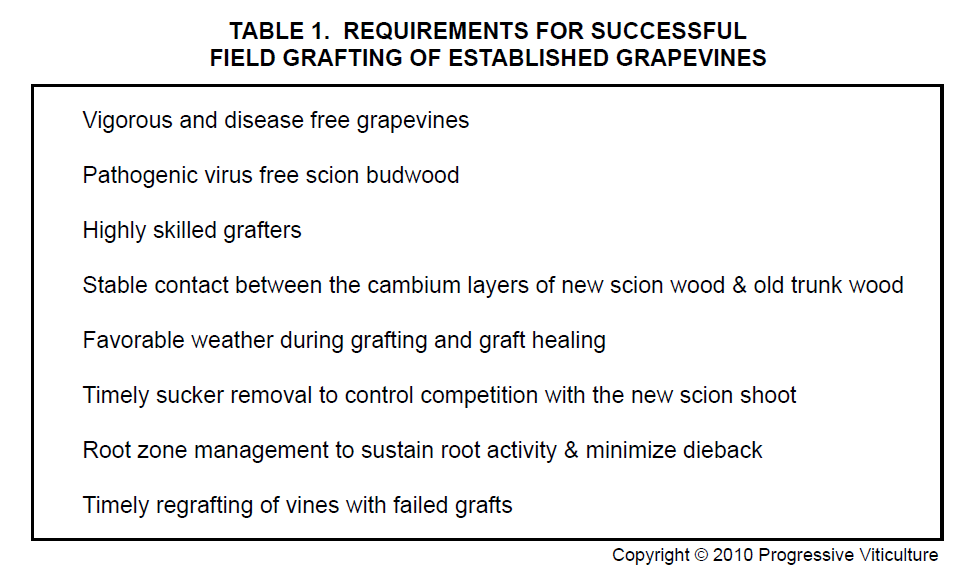

On the other hand, grafting an existing vineyard is a viable option where vines are healthy, the rootstock is appropriate for the site, and vineyard hardware is sound. This option, however, involves some risks, which must be considered and as much as possible, controlled (Table 1). Virus-tested, CDFA certified scion bud wood of the new variety is a necessity for any successful grafting endeavor. The scion budwood must also be well-formed, well-nourished, and dormant, but somewhat acclimated to ambient air temperatures. Another essential factor is a reliable and highly skilled grafting contractor dedicated to your variety conversion success. The contractor’s commitment ought to include prompt regrafting of vines with initial grafts that failed.

Methods of Grafting Established Vines

There are several methods for grafting established vines. Curtis Alley of the UC Viticulture and Enology Department evaluated most of them. Top working, which is grafting well above the soil surface, is another name for these techniques. In California, the side whip graft and the T-bud graft are among the most commonly used methods for top working grapevines.

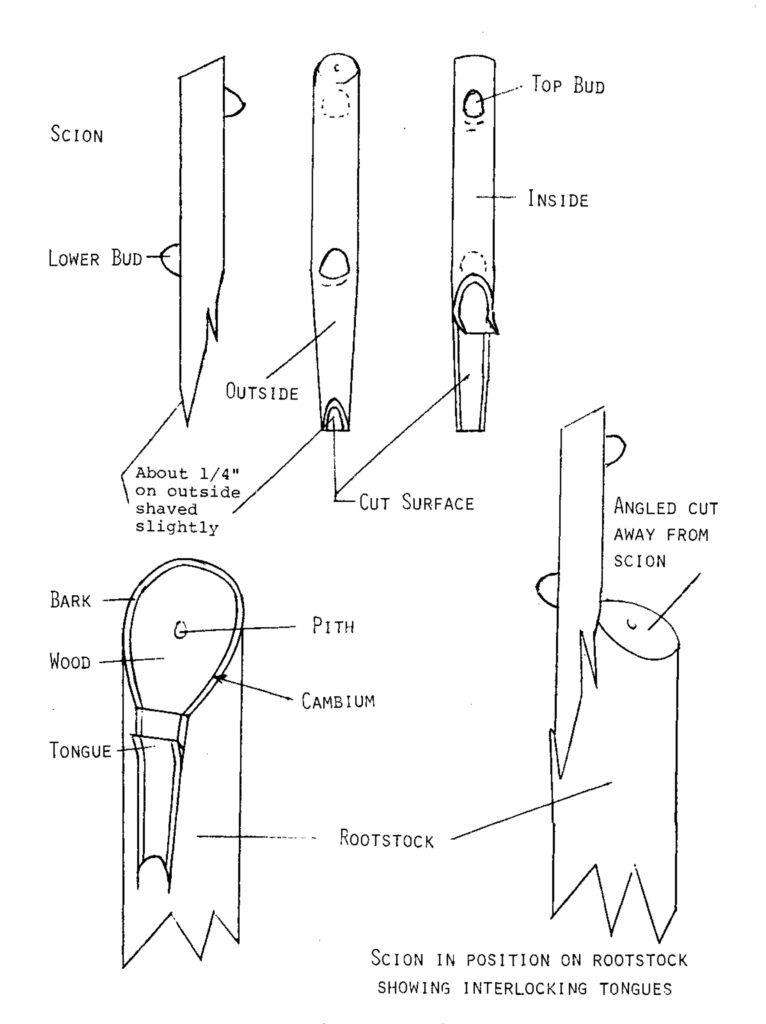

With the side whip graft, a cane section of the new variety is positioned partially on top of the cut trunk stump of the old vine and partially on the side of the trunk, while the T-bud graft positions the new variety entirely on the side of the trunk of the old vine. Further, the whip graft uses a short section of scion cane that may include two buds, while the T-bud uses a single scion bud attached to a small amount of cane wood (the shield).

The side whip graft offers some important advantages of other grafting methods involving cane sections near the top of trunk stumps, including the cleft, notch, and bark graft. First, it provides extensive contact between outer generative tissues (cambium) of the new scion and the old vine, which must grow together to complete the graft (Figure 1). Second, the scion bud stick and the old vine trunk wood fit together tightly and as a result, the graft is comparatively stable. Both of these factors increase the chances of grafting success. Additionally, side whip grafts may be made earlier than a T-bud graft. On wider trunks (2.0-inch diameter or more), two scion sticks are grafted on opposite sides of the old vine trunk to increase the odds of grafting success and to keep more of the old trunk alive.

T-bud grafting (a.k.a. T-budding or shield budding) is the preferred grafting method for windy areas, but it is also widely used elsewhere in California. In addition, T-bud grafting is regularly used to replace failed whip grafts. This grafting technique acquired its name from the T-shaped incisions made in the bark on the side of the trunk of the old vine. A scion bud, excised from the bud stick and attached to a small amount of woodcut flat on the back, is inserted lengthwise and downward behind the vertical bark incision and below the horizontal incision. When properly positioned, only the bud is visible on the outside of the graft (Figure 2). Like the side whip graft, two T-bud grafts are usually made on opposites of vines with sufficiently wide trunks.

Typical Grafting Procedure

The onset of early-season cambium tissue activity in the old trunks is a typical time of top working vines, although as mentioned above, side whip grafts may be made earlier. Cambium activity is evident as bark slippage. In California, grafting commonly occurs during April and May, after a significant threat of frost. Callus development and graft healing precede best under the moderate temperatures and moderate humidity prevalent during this time.

Sometime prior to grafting, the cordons are cut from the trunk and removed from the vineyard. Immediately before grafting, the trunk receives a horizontal cut at least 10 to 12 inches below the cordon wire to expose fresh wood and at the height that facilitates retraining.

After grafting, the graft is wrapped and stabilized with white grafting tape. Where old vine trunks bleed profusely, the grafter may make 2 diagonal incisions about 1 inch apart and 6 inches below the graft to redirect sap away from it. After the sap stops flowing, the cut surface of the stump is protected with fungicides (e.g. Topsin, Rally, and/or boric acid) mixed with a penetrant or latex paint.

Post Grafting Events and Care

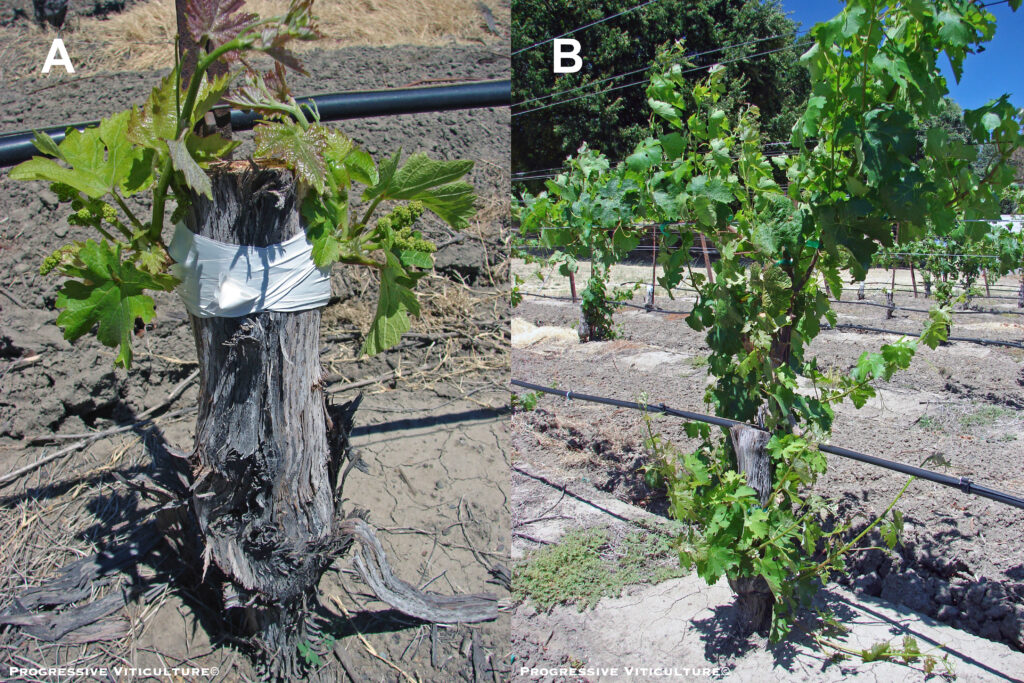

Figure 3. Opposing T-bud grafts on a mature Petite Sirah trunk (A) shortly after successful Cabernet Sauvignon shoots emerged from grafted buds and (B) after trunks and partial cordons were trained (sucker removal is needed). (Photo Source: Progressive Viticulture©)

New scion shoots appear after a few weeks, but often these primary shoots fail. A few weeks later, secondary shoots emerge. A shoot that elongates to a length of at least 1/2 inch is the criterion for a successful graft (Figure 3A). Replace failed grafts as soon as possible (usually 4 to 6 weeks after initial grafting) to promote vineyard uniformity and maximum productivity.

Successful scion shoots from new grafts often grow rapidly, as much as 1 inch per day. Initiate vine retraining after scion shoots have extended about 12 inches beyond the cordon wire. Often, over a few weeks, new cordons are fully extended and tipped to force lateral shoots to form new spur positions (Figure 3B). On some varieties, lateral shoots on new cordons yield a second crop at economic levels. In the second year after grafting, vines often produce near-normal fruit yields (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Complete Cabernet Sauvignon canopies and normal crops on Tbud grafted Petite Sirah grapevines. (Photo Source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Variety Conversion Summary

There are two options for changing varieties in vineyards. Of the two, vineyard replacement is more expensive, while grafting is riskier. Before moving forward with either of these options, carefully consider all vineyard and market factors to ensure the best possible outcome. And after making the replacement decision, use the best available resources and methods to ensure a successful variety change.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services March 2010 newsletter and was updated for this blog post.

Further Reading

Alley, CJ. Grapevine propagation. I. A comparison of cleft and notch grafting; and, bark grafting at high and low levels. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 15, 214-217. 1964.

Alley, CJ. Grapevine propagation. VII. The wedge graft – a modified notch graft. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 26, 105-108. 1975.

Alley, CJ. Grapevine propagation. VIII. The side whip graft, an alternative method to the split graft for use on stocks 2-4 cm in diameter. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 26, 109-111. 1975.

Alley, CJ. T-bud grafting of grapevines. Calif. Agric. pp. 5-6. July, 1977.

Alley, CJ, Neja, RA, and West, TA. Grapevine propagation. X. Effects of tape color, wax type, bud covering, and early topping on late spring chip and T-budded vines in Greenfield, Monterey County, California. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 30, 1-2. 1976 and 1979.

Alley, CJ. Chip-budding of mature grapevines. Calif. Agric. pp. 14-15. 1979.

Alley, CJ, and Baron, DH. Grapevine propagation. XV. Comparison of long and short bud shield below the bud; and standard and inverted bud cut in T-budding at high level. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 31, 95-97. 1980.

Alley, CJ, and Koyama, AT. Grapevine propagation. XVI. Chip-budding and T-budding at high level. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 31, 60-64. 1980.

Alley, CJ, and Koyama, AT. Grapevine propagation. XIX. Comparison of inverted with standard T-budding. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 32, 29-34. 1981.

Alley, CJ. Grapevine propagation. XVIII. Spring chip-budding of mature grapevines at high level from February through April. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 32, 26-28. 1981.

Alley, CJ, and Gallagher, SF. Side-whip grafting of grapevines to change over varieties. Calif. Agric. pp. 8-9. March-April, 1983.

Gale, EJ, and Moyer, MM. Field grafting grapevines in Washington State. Washington State University Extension. Undated.

Galet, P. General viticulture. Oenoplurimedia, Chaintre, 2000.

Jensen, F. High level grafting of grapevines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 22, 35-39. 1971.

Nicholas, PR, Chapman, AP, and Cirami, RM. Grapevine propagation. In Coombe, BG, and Dry, PR (ed.). Viticulture. Volume 2 Practices. Winetitles, Adelaide. pp. 1-22.1992.

Steinhauer, RE, Lopez, R, and Pickering, W. Comparison of four methods of variety conversion in established vineyards. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 31, 261-264. 1980.

Winkler, AJ, Cook, JA, Kliewer, WM, and Lider, LA. General Viticulture. Univ Calif Press, Berkeley, 1974.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.