MONDAY, JUNE 5, 2023. BY STEPHANIE BOLTON, PhD, LODI WINEGRAPE COMMISSION.

Today, most winegrowers are aware of the high risk for leafroll virus infection when there are mealybugs in their vineyard and/or in neighboring vineyards. Mealybugs and scale insects are vectors of (meaning they spread) leafroll virus and a group of viruses called vitiviruses (GVA, GVB, etc.). Leafroll virus reduces a vine’s ability to photosynthesize, making it difficult or even impossible to ripen grapes in some cases and vintages. It can also lower yield which reduces the profitability of a vineyard. On several common rootstocks which are more sensitive to leafroll virus, a co-infection of leafroll and vitiviruses plus added stress (crop stress, water stress, trunk disease, etc.) can lead to a disease we named sudden vine collapse. Growers across California have painfully watched entire sections of their vineyards die off. Right now during flowering, sudden vine collapse symptoms look like patches of dead and missing vines with vines showing stunted shoot growth on the edge of the death patch.

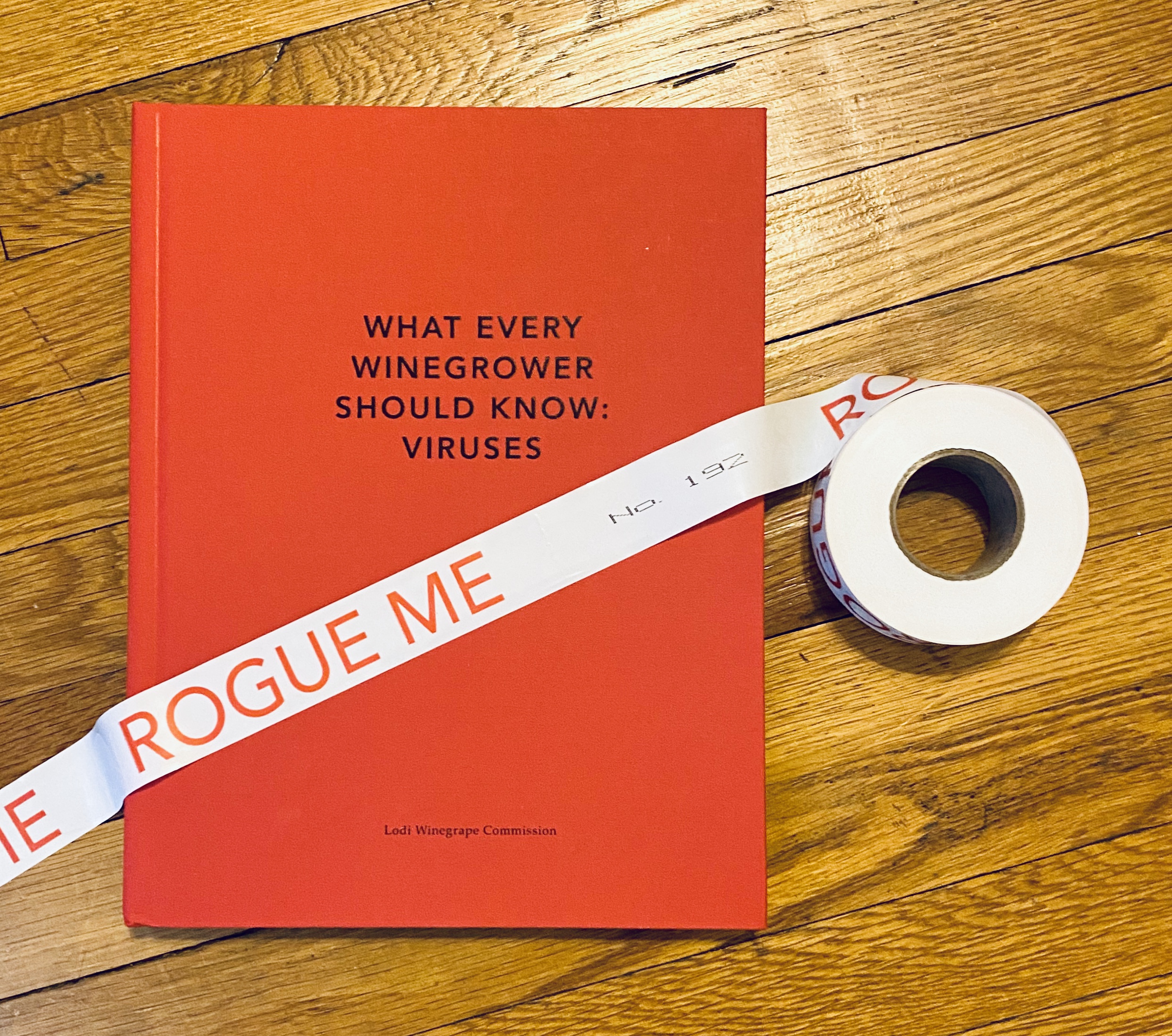

At the Lodi Winegrape Commission, we have intensely, holistically, and collaboratively studied our local vine mealybug and grapevine virus situation since 2002. We still have a lot to learn, and we work tirelessly to pass along our findings as we go because we believe in learning together and the power of teamwork in overcoming big challenges. Through many, many long conversations between growers, pest control advisors, nurseries, laboratories, scientists, industry, and others we have discovered the various options available for mealybug control, virus testing, and rogueing (grapevine removal). We gathered information from our local region, from California, and beyond and shared it in our red virus book, What Every Winegrower Should Know: Viruses (2020, Lodi Winegrape Commission).

At the Lodi Winegrape Commission, we have intensely, holistically, and collaboratively studied our local vine mealybug and grapevine virus situation since 2002. We still have a lot to learn, and we work tirelessly to pass along our findings as we go because we believe in learning together and the power of teamwork in overcoming big challenges. Through many, many long conversations between growers, pest control advisors, nurseries, laboratories, scientists, industry, and others we have discovered the various options available for mealybug control, virus testing, and rogueing (grapevine removal). We gathered information from our local region, from California, and beyond and shared it in our red virus book, What Every Winegrower Should Know: Viruses (2020, Lodi Winegrape Commission).

Despite making significant strides towards understanding this issue and increasing our efforts in the vineyards, we realize that the battle to keep our vines healthy is far from over.

The great California mealybug and virus challenge is at the front of our minds, and the members of our Virus Focus Group continue to strategize and bring outside-the-box thinking in an effort to keep our farms sustainable. At parties you can inevitably find us in the corner somewhere engaged in a discussion about the best ant control (this happened at a graduation party last night – current theory is two applications of Esteem applied with a herd spreader). After a few glasses of wine, we act out vine mealybug parasitism by the Anagyrus wasp to new friends (a B’nai Mitzvah in April). Dr. Keith Striegler sends us articles every few months on the exemplary boll weevil eradication in cotton as inspiration. Mealybugs invade our nightmares. We dazzle fellow vacationers with our documentary-worthy story (thank you, sweet Irish woman on the Great Barrier Reef cruise). Charlie Starr IV twisted pheromone mating disruption onto my Jeep’s side-view mirrors. In short, we are committed to finding a way out of this mess and at the same time, our friends and family are quite ready for new conversation topics.

Through these fascinating discussions and by visiting farms across the globe, I’ve come to realize that California has unique challenges around mealybugs and leafroll virus that are critical for us to understand:

1. Our main destructive mealybug species, the vine mealybug, spreads leafroll virus particularly well.

The vine mealybug has 5-7 generations (life cycles) per year. However, the two main mealybug species of concern in New Zealand, citrophilus and obscure mealybugs, only have 3 generations, making their overall numbers lower. Our warmer winters are not helping our situation either, as insect generations mainly depend on temperature.

2. The synthetic plant protectant tools for mealybug IPM (integrated pest management) are becoming unavailable.

South Africa leads the world in their country’s ability to control leafroll virus. The backbone of their program is a material called imidacloprid, whose use will soon be restricted in California.

3. Mealybugs and viruses are moving through our supply chain.

It is bad business but not illegal to sell vines carrying mealybugs or leafroll virus. As a state, we didn’t establish the invasive vine mealybug as a quarantine pest early on though we should have (lesson learned – the spotted lanternfly is a quarantine pest). Growers are still unknowingly planting fields of vines infested with mealybugs and infected with leafroll virus. It’s the responsibility of nurseries and growers to do their part to plant clean material. We can’t state the importance of checking under the wax at the graft union for mealybugs and of doing an extra set of virus testing for leafroll and red blotch viruses (above and beyond the CDFA grapevine certification!) enough. New plantings with a problem then serve as a host for mealybugs and viruses to spread throughout the neighborhood and region. At this stage in our crisis, once mealybugs are present in a vineyard, they cannot be eradicated. Hopefully one day that will change. We hope that canine detection of mealybugs and viruses in nurseries and new vineyard plantings would help.

4. Most California vineyards have external crews, vehicles, and machinery moving through them.

Without a sanitation protocol in place, each time a crew, a vehicle, or a piece of equipment comes into your vineyard during the growing season, there is potential for them to bring in virus-infected mealybugs with them.

5. Many vineyards in California are very close to (within meters of) vineyards owned by someone else.

It’s difficult to accept, but we can control very few things in life. One of the things we cannot control is what happens in our neighboring and regional vineyards that we do not manage. If there is a vineyard with mealybugs and leafroll virus upwind of yours, you are at greater risk to become infested and infected yourself. California has areas that look like patchwork quilts of vineyards with different owners. In Uruguay, for example, vineyards with different owners are much more spread apart with miles of natural areas between them.

6. There are fewer physical barriers around our vineyards than in other parts of the world.

As you drive through California you will find areas of the state where there are back-to-back vineyards for miles. We just mentioned Uruguay where farms are surrounded by wild, natural areas. In New Zealand, farms are bordered by windbreak hedgerows (pictured as the dark green areas to the left above Auckland). Both scenarios offer a natural barrier which also provides habitat for beneficial insects. Our rate of infestation with mealybugs and infection with viruses is therefore much faster. Last week, two separate growers told me that they saw vine mealybugs in their new vineyard plantings within the first three months. Crop rotation and farm diversification are becoming increasingly important as the disease risk increases along with the cost to establish a new vineyard.

7. We have a shortage of labor that drives mechanization.

Machine harvesting is a high-risk activity when it comes to mealybug and virus infections. Both the mealybug populations and the amount of leafroll virus present in a grapevine are at their peak during harvest. Imagine the spray of infected mealybugs that happens as a harvester moves down a row. Does your custom harvester sanitize their equipment with a disinfectant before it enters your vineyard? We have the potential for another fast and furious harvest in 2023. Before it starts, have the conversation needed to understand what can be done to ensure sanitation of equipment.

8. Many of our vineyards have been under drought and/or crop stress.

A little stress is good for wine quality because the plant produces antioxidants in response to stress which improve anthocyanin production, increasing color and flavor in the grape berries. Too much stress, however, can have detrimental effects on plants just like it does in humans. California has recently experienced both a severe drought and an oversupply of winegrapes leading to low prices, encouraging high yields to keep vineyards in the ground (further exacerbating virus disease and our oversupply problem).

9. The majority of our vineyards are owned separately from their winery buyer.

If a winery owns virus-infected vineyards, they have a vested interest in cleaning them up to raise wine quality. They also have an inherent desire to protect their vineyards from vine mealybugs, and they understand the added cost in doing so. A significant portion of growers in California, however, sell their grapes to outside winery buyers. Caine Thompson, who helped lead a successful regional leafroll virus eradication program in Gimblett Gravels, told us that wineries play a key role in reducing virus infections. Once the wineries understand that grapevine viruses are an industry-wide problem (not a grower’s problem), they can work with the growers to transition into cleaner vineyards over time. We do not have the winery buyers on board yet. Instead, too often we observe a winery cancel a contract with a grower whose virus infections are inhibiting ripening and offer a new planting contract at a price too low to ensure adequate mealybug and virus management.

10. Virus testing is particularly expensive and laboratories operate without oversight.

In South Africa, it costs about $5 USD to test a vine for leafroll virus. In the US, this may cost $75 plus overnight shipping. The virus testing laboratories have actually asked us (the Lodi Winegrape Commission) to help them ensure accurate testing by sending them blind samples and to help them get official accreditation for grapevine virus testing. Due to the hurdles around virus testing, many growers choose to simply not know which viruses their vineyards are infected with. By the time they test, it is usually a shocking surprise to see how many viruses exist in a single block.

11. Our farm biosecurity for vineyards is almost non-existent.

Between March to April this year, I traveled to Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia and Japan. Each time I entered a country I was asked if I had been on a farm…except for when I returned to the United States. Instead, the customs officer in San Francisco asked me if it was hot in Lodi, to which he got a thorough response about our cooling Delta breezes and large diurnal swing which creates an excellent climate for winegrapes. Indonesia had better biosecurity. Before we walked onto even a backyard farm with four cows, we dipped our boots into a sanitizing solution. We saw trucks and people get washed down before they entered a cattle feedlot (pictured above). This same ranch also had a separate, quarantined parking area for the motorcycles that the many, many employees rode into work (they planted 80 hectares of corn by hand there!). In Japan, we wore disposable booties in every field. We drove through tire washes in Australia’s northern Tablelands where the banana industry is terrified of Panama disease tropical race 4.

12. Many of our vineyards are very large.

When some Italians visited us, they could not believe how long our rows of vines were. Even with a plethora of technology to help monitor our vineyards, it is still quite difficult to notice an early infestation of mealybugs or to map which vines are symptomatic for leafroll virus (remembering that for white grape varieties, this is nearly impossible) when a vineyard is over about 20 acres.

13. There is a considerable amount of leafroll virus present in our vineyards across the state.

Without infected vines, the mealybug problem would not be so huge because the mealybugs would not have virus to spread. This is why rogueing, or removing infected vines, is so important. There are different theories floating around as to why (AXR1 was hiding it, planting booms, etc.), but we can all agree that there is simply too much leafroll out there today.

Knowing these California-particular challenges will help us understand how to best protect the next generation of our vineyards. It is clear that we need better and earlier detection methods for vine mealybugs and leafroll virus, and we are hoping that canines can help us with that.

Tomorrow at our monthly IPM meeting, I will lead participants in a farm biosecurity exercise to create a vine mealybug prevention map for their most prized vineyard. If it goes well, we will post a how-to for others as a future blog.

We are lucky to work in an industry that has already overcome both phylloxera and Prohibition, so we know how to get through tough times. We can do better. Knowledge is power. Teamwork is crucial.

Send your ideas and thoughts to stephanie@lodiwine.com.

Thanks to Chris Storm and Stuart Spencer for their excellent insight around our great mealybug and virus challenge, and for reviewing this article.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.