Solving vineyard problems can be a complex and time consuming task, as is deciding how to correct them. The most obvious remedy is sometimes taken to be the most practical while, in reality, it treats the symptoms rather than the cause of the problem. In this article, we will consider some of these instances.

Solving vineyard problems can be a complex and time consuming task, as is deciding how to correct them. The most obvious remedy is sometimes taken to be the most practical while, in reality, it treats the symptoms rather than the cause of the problem. In this article, we will consider some of these instances.

Multiple Hedging Passes

Hedging, which is also sometimes called topping or tipping, increases the uniformity of shoot lengths and canopies, and correspondingly, a vineyards’ ripening capacity. Making a hedging pass through a vineyard is, therefore, a reasonable thing to do. Multiple hedging passes, on the other hand, are a fuel and labor consuming band-aid that masks factors inducing prolonged and excessive shoot growth (Figure 1). In addition, it stimulates the growth of lateral shoots that shade fruit zones, compromising disease control and grape quality.

Figure 1. Hedging excess shoot growth is viticulturally inefficient.

Photo source: Progressive Viticulture, LLC ©

Factors inducing excessive shoot growth include surplus soil water or nitrogen. In these cases, reduced water and fertilizer applications or competitive cover crops are true remedies.

Alternatively, an ill suited vineyard design may be the cause of excess shoot growth. Such designs allow too few buds and shoots per vine to absorb the growth capacity inherent in the combination of site, variety, and rootstock. To dilute growth, a grape grower could increase the number of spurs at each position (i.e. double-spur pruning). Doing so, however, also increases canopy density and associated fruit zone shading. The ultimate solution involves structural changes, like canopy division or alternating vine removal followed by cordon extension on the remaining vines.

Kicker Canes

Kicker canes are a convenient way to increase fruit yields of cordon trained vines. Simply retain one or more cane per cordon during pruning and tie it to a foliage support wire to significantly increase the number of buds and fruit bearing capacity (Figure 2). But are kicker canes viticultural band-aids? Are there downsides to kicker canes? And what makes kicker canes necessary?

The answer to the first question is “yes” they are viticultural band-aids. The answer to the second question is also “yes”; there are downsides. Kicker canes create a second, higher positioned and lower vigor fruit zone that complicates disease control, fruit quality management, and harvest scheduling.

The answer to the third question has something in common with hedging. The need for additional bearing units in the form of kicker canes is a consequence of too few spurs per vine, which in turn is the result of an inappropriate spacing-training-trellising-pruning system (i.e. vineyard design). Again, the optimum solution is a structural one, such as converting bilateral to quadrilateral cordons.

Adding Emitters on Existing Drip Hose

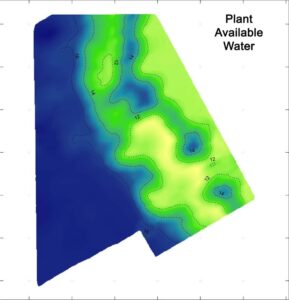

Some grape growers insert extra drip emitters in areas of restricted vine growth to increase quantities of applied water and fertilizer to the drip zone. While this effort may increase vineyard uniformity to some degree, it fails to address the causes of the variability, which typically involve water holding capacity and fertility in the soil beyond the emitters (Figure 3). Moreover, this band-aid may have serious side effects.

Figure 3. A vineyard soil water holding capacity map with high water holding capacity shown in blue and low water holding capacity shown in yellow.

Photo source: Progressive Viticulture, LLC ©

Extra emitters, while increasing water flow in the restricted growth area, correspondingly decrease water flow elsewhere in the vineyard. At the same time, pressure within the system drops and to some degree, drip system performance diminishes. These effects are contrary to the objective of drip irrigation, which is uniform distribution of water and applied chemicals across a vineyard to promote uniform vine growth and fruit production.

Rather than altering a drip irrigation system, alter irrigation schedules. All vines within a vineyard have the same potential leaf area and correspondingly, the same need for water. The remaining questions are when to start and how often should water be applied. The answers are as soon and as often as needed to maintain an available supply of soil moisture in the area of lowest water holding capacity. Such scheduling, along with organic matter and nutrient additions to restricted growth areas, is ultimately more effective and less disruptive than extra drip emitters.

Nematicides

Chemical control of soil borne pests is the last line of defense in established vineyards. In effect, reliance on nematicides represent failures of other nematode control methods, including preplant fumigation, resistant rootstocks, suppressive soil environments created through rotating cover crops composed of diverse species (Figure 4), and intensified application of organic matter, water, and mineral nutrients to compensate for root damage. At least for vineyards, nematicides are pest management band-aids.

Figure 4. Soils supporting only grapevines have relatively small, low diversity soil microbe populations, which makes them favorable environments for plant parasitic nematodes.

Photo source: Progressive Viticulture, LLC ©

Conclusions

While bailing wire, zip ties, or duct tape may keep a piece of field equipment running long enough to finish a job, they are neither reliable nor durable solutions to a problem. Viticultural band-aids are very much the same, but the problems they address are of much greater significance for vineyard businesses. In this article we examined four such band-aids, but there are undoubtedly more. For the sake of operating efficiency, fruit yield and quality, and vineyard profitability, all of them warrant fitting solutions.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services May, 2016 newsletter.

Further Reading

Burt, CM; Styles, SW. Drip and microirrigation for trees vines and row crops (with special sections on buried drip). Irrigation Training and Research Center, Department of Agricultural Engineering, California Polytechnic. State University, San Luis Obispo. 1994.

Ferris, H. Contribution of nematodes to the structure and function of the soil food web. J. Nematol. 42, 63-67. 2010.

Ferris, H Zheng, L; Walker, MA. Resistance of grapevine rootstocks to plant parasitic nematodes. J. Nematol. 44, 377-386. 2012.

Goldhammer, DA; Snyder, RL. Irrigation scheduling: a guide for efficient on-farm water management. University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 1989.

Grant, S. Five-step irrigation schedule: promoting fruit quality and vine health. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 21(1):46-52 and 75. May/June 2000.

Hanson, B; Orloff, S; Sanden, B. Monitoring soil moisture for irrigation water management. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 21635. 2007.

Howell, GS. Sustainable Grape Productivity and the Growth-Yield Relationship: A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 52:165-174. 2001.

Jackson, DI: Lombard, PB. Environmental and management practices affecting grape composition and wine quality – A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 44, 409-430. 1993.

McKenry, MV; Bettiga, LJ. Nematodes. In Grape Pest Management. 3rd ed. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 3343. pp. 149-470. 2013.

Schwankl, L; Hanson, B; Prichard, T. Micro-irrigation of trees and vines: a handbook for water managers. University of California Irrigation Program, University of California, Davis. 1995.

Shaulis, NJ. Responses of grapevines and grapes to spacing of and within canopies. In A. Webb (ed.). Grapes and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings, Davis, Calif., 18-21Jun. 80. Univ. Calif. 1982.

Smart, R. and M. Robinson. Sunlight into wine: A Handbook for Winegrape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1991.

Winkler, AJ; Cook, JA; Kliewer, WM; Lider, LA. General Viticulture. University of California, Berkeley. 1974.

Zasada, IA; Ferris,H. Nematode parasites of grapes. In Compendium of Grape Diseases. 2nd ed. Wilcox, WF; Gubler, WD; Uyemoto, JK (ed.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN. pp. 138-146. 2015.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe” or click on “join our email list” to the right.

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.