MONDAY, AUGUST 16, 2021. BY RANDY CAPAROSO.

Terroir is a French term that entails the natural environmental factors, such as climate, soil, topography, aspect, elevation, latitude, etc., that have a direct effect on grape qualities, and ultimately on wines made from those grapes.

Second, because vineyards, like wines, involve human input, viticultural traditions closely associated with regions or eras are often considered part of a region’s or vineyard’s terroir.

Third, the word terroir is also frequently applied to sensory qualities in resulting wines in terms of their expression of “sense of place,” especially when there is less priority placed on qualities such as varietal character or brand style. On a sensory level, a wine’s expression of terroir is not necessarily, as the word implies, an earth- or mineral-related quality, although earthy or minerally qualities can certainly be part of it. The predominant sensory perceptions of terroir in a wine usually have more to do with qualities of aroma and palate sensations such as body (closely related to levels of alcohol in wine), acidity, and tannin.

Michael David Winery VP of Operations Kevin Phillips with Petite Sirah, his favorite Lodi-grown grape for both blending and varietal bottlings.

The Terroir-related Aspects of Commercial Style Lodi Wines

But is terroir an important factor in the production or appreciation of commercial wines? Yes and no. For example, Lodi‘s most successful family-owned winery, Michael David Winery, focuses primarily on wines branded with thematic iterations of either varietals (i.e., wines focused on grape-related characteristics) or whimsically labeled brands (labels such as Freakshow, Earthquake, Inkblot, Lust, Rapture, etc.).

Two exceptions in Michael David’s portfolio are vineyard-designate bottlings of red and rosé Cinsauts sourced from the fabled Bechthold Vineyard, which the winery crafts to be true to the fragrant, subtlely earth/mineral/spice profiles of the grapes growing in this 135-year-old vineyard (Lodi’s oldest continuously farmed block of own-rooted vines). These are Michael David’s only wines grown and produced to express one vineyard’s terroir, at least in the purest sense of the word.

All of Michael David’s other Lodi appellation wines are blends of both numerous vineyards and often multiple grapes. Petite Sirah, for instance, is a favorite blending grape, going into Zinfandels as well as other varietal bottlings such as Cabernet Sauvignon (VP of Operations Kevin Phillips is so fond of Petite Sirah, he has jokes that if he could blend Petite Sirah in with Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc, he would!).

Otherwise, the primary objectives of Michael David’s blending program are to produce wines that are: 1) intense, compelling yet highly accessible; and 2) reflections of consumer-friendly qualities intrinsic in grapes grown in Lodi, which is proudly displayed as the appellation on Michael David labels (note: Michael David does produce a handful of wines from appellations other than Lodi, which are duly noted on labels).

As such, Michael David’s wines could be described as wines that express the Lodi appellation in the very broadest of terms: That is, the region’s natural propensity to produce red wines with softer tannin yet are pungently aromatic, as well as fresh, fruit-forward whites that are, collectively, very commercially appealing. You could, in fact, describe these generalized wine profiles as reflections of a regional terroir — the direct results of Lodi’s warm, sun-soaked Mediterranean climate and variety of extremely grape-friendly, rich yet well-drained soils.

Michael David has not only wholly embraced the sensory ramifications of Lodi’s overall terroir, it has taken them all the way to the bank. This is precisely why all of Lodi’s 800-odd growers and winery-colleagues credit the Phillips family of Michael David Winery for doing more to promulgate the Lodi appellation around the world than any other homegrown company.

Highly detailed front and back label typical of LangeTwins Family’s new line of single-vineyard wines.

To give credit where credit is due: Other Lodi-based wineries owned and operated by longtime Lodi families who have done terrific jobs getting wines with Lodi on the label onto the tips of tongues and in the minds of consumers across the country and around the world include Klinker Brick Winery, LangeTwins Family Winery & Vineyards, Ironstone Vineyards, and Mettler Family Vineyards.

Growing Pains of Terroir-Focused Wines In the American Wine Industry

Wines labeled with single vineyards as exclusive sources of wines tend to be implicitly terroir focused — coming to you with expectations that what you get in the bottle is strongly indicative of sensory qualities resulting from growing conditions associated with a specified vineyard. The reality, however, is that this is not always what happens. In fact, for a long time, American wine producers considered sensory qualities resulting directly from vineyards terroirs to be far less important than other factors — even in wines with single vineyards cited on the label.

Barrel toasting in cooperage — the selection of which by winemakers has a huge impact on the house styles of wineries and sensory profiles of subsequent wines.

For example, there are numerous wineries that put out multiple wines each year bearing vineyard designations on labels — wines made from Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot noir, Grenache, Mourvèdre, you name it — yet when you taste each of those wines (if made from the same grape), they taste almost exactly alike, as if vineyard differentiations don’t matter. The reason for this, to put it bluntly, is because of either

• Winemaker egos (frankly, the majority of American winemakers are obsessed with placing their personal stamp on wines, like “artists,” regardless of vineyard sources), or

• “House” styles of wineries (in the U.S., part of identifiable branding more often than not involves making sure all the products within a winery’s portfolio possess a commonality of certain sensory qualities).

(From left) Lodi-grown Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Zinfandel — three different winegrapes which will invariably end up with similar sensory qualities when fermented with the same yeasts, following the same protocols, and using the same oak adjuncts or aged in the same type of barrels, which are not uncommon practices in many wineries.

These circumstances have been part and parcel of the growing pains of the American wine industry. Both wineries and winemakers, for one, tend to favor oak barrels from particular cooperages, finished with certain “toast” levels (degree of charring over fires during the barrel coopering process). Consequently, it is not uncommon to taste through, say, one winery’s Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Zinfandel, Grenache, and Petite Sirah, and find that all these wines taste alike — mostly because they were all aged in exactly the same types of barrels.

The marketing of many commercial American wines is driven by numerical ratings accorded by a few widely read publications — especially for super-premium priced, “artisanal” style wines, the sales of which are dependent upon 90+ scores. Therefore, the typical approach to wine production is to have grapes picked as ripe as possible (based on the premise that the riper the grape, the more intense the varietal character, which leads to higher scores and thus more demand and sales), and then to simply “adjust” the wines once they are in the winery (i.e., adding water to lower alcohol levels, adding acids and/or oak amendments to balance sensory qualities, utilizing specific yeast strains to achieve specific, desired aromatic effects, etc.).

2010 blind tasting of 25 Oregon Pinot noirs contrasting vineyards vs. winemaking styles. Image courtesy of Oregon Wine Press.

True story: Eleven years ago I conducted a blind tasting of 25 Pinot noirs crafted by five of Oregon’s most prestigious wineries, each producing a wine from the exact same batches of grapes picked in each of the five wineries’ most important vineyard. In other words, each winemaker made a Pinot noir from the other winemakers’ grapes.

I invited five top, experienced sommeliers from the Portland/Willamette Valley area to blind-taste all 25 wines at once, to see if they can make out the differences between them. Only one of the five sommeliers was able to recognize the five different vineyards. The other four sommeliers mistakenly identified the different winery styles as being reflections of the different vineyard sources. In other words, even to these savvy sommeliers, the winemaking styles of these Pinot noirs had a far greater impact on the overall sensory qualities than vineyard distinctions!

Does this mean that vineyards in Oregon are incapable of expressing terroir? Of course not. It just meant that, at that point in time, Oregon’s top winemakers were more focused on producing Pinot noirs in their individual house style than on Pinot noirs expressing sensory qualities intrinsic to individual vineyards. In fact, that was probably their point. Even though there was an acknowledgment of individual vineyard sources, vineyard terroir simply wasn’t that important.

I like the way one longtime California winemaker/friend once described the difficulty of the American wine industry, in general, has had making the transition to a more genuine focus on terroir, away from sensory profiles prioritizing varietal character or brand styles: “Terroir is elusive, subtle and difficult conceptually, but just because it is subtle does not mean it is not real.”

Cabernet Sauvignon grown in LangeTwins Family’s Railroad Vineyard, which goes into a single-vineyard bottling

Vineyard-Designate Lodi Wines Achieving Varying Degrees of Terroir

Lodi is no exception — there are more than a few locally based brands that tend to cling to house styles, or wines prioritizing winemaker sensibilities over vineyards or even broadly defined regional characteristics. But as with other wine regions, Lodi has been making rapid progress over the past ten, fifteen years with wines that are increasingly capturing qualities specific to Lodi in general, or to individual vineyards within the Lodi appellation.

In the following list of wines currently labeled with single-vineyard identifications, you would have to be your own judge as to how successful each winery is in capturing vineyard terroir. You may personally find, for instance, that some Lodi vineyard-designate bottlings taste more like a winery’s style, their barrels, or more of an adherence to varietal profile than an actual vineyard. In many cases, you may not recognize an individual vineyard’s terroir-related characteristics simply because of unfamiliarity — vineyard characteristics may not have established a track record with you.

LangeTwins Family, for one, has justifiably earned accolades from many quarters for their recently established line-up of vineyard-designate wines made from a battery of varieties, mostly Italian. But even the Langes’ talented duo of winemakers, David Akiyoshi and Karen Birmingham, would agree that it will take another ten or fifteen years before we all have a strong sense of each of these individual growths — what to expect, or (on the winemakers’ part) how to capture it. But they are as excited as anyone by the discovery process!

Well-established track records are obviously found in bottlings from better-known vineyards, such as Bechthold Vineyard’s Cinsaut, from which about a dozen vintners produce a red or rosé each and every year. Among Lodi’s vaunted ancient vine Zinfandels, Rous Vineyard is one of the region’s more minuscule plantings — just 10 acres of vines planted in 1909 — but sensory qualities (violet/floral notes piled upon plump, blueberryish fruit sensations) already common to bottlings by Ironstone Vineyards, McCay Cellars, as well as Macchia Wines, have firmly established a distinct “Rous” identity — something that can only be chalked up to a unique, one-of-a-kind terroir.

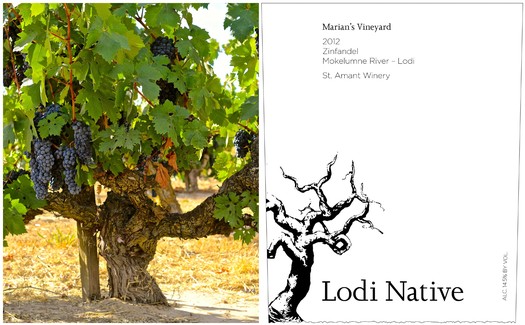

120-year-old Zinfandel in Marian’s Vineyard (left) going into Lodi Native Marian’s Vineyard bottling (label on right) each year since 2012.

One gigantic step towards terroir-focused winemaking has been led by an ongoing project called Lodi Native which, starting with the 2012 vintage, has involved winemakers voluntarily pulling back on their personal or house styles to produce Zinfandels highlighting heritage vineyards, front, and center. It is the Lodi Native project, plus the labors of other independent wineries, that has recently led to the recognition of distinctive sensory markers imparted in Zinfandel plantings such as:

• Lot 13 Vineyard (very fragrant, feminine, red berry scented reds by McCay Cellars)

• Kirschenmann Vineyard (exquisitely delineated, multi-scented wines by Turley Wine Cellars, Sandlands and Precedent Wine)

• Lizzy James Vineyard (red berryish fruit manifested in full yet elegantly balanced layers)

• Stampede Vineyard (known for edgy acidity and grippy tannin offsetting flowery red fruit)

• Marian’s Vineyard (St. Amant Winery‘s iconically full, plush, earth nuanced vintages)

• Wegat Vineyard (flowery blue and dark berry notes juxtaposed with loamy undertones)

• Soucie Vineyard (opulent fruit with a pungent earthiness personified in m2 Wines bottlings),

• TruLux Vineyard (essence of the fleshy, dark fruit-toned, rustic/earthy style of Lodi’s “west side”).

Lodi Native winemakers and growers (2013 portrait, from left): Layne Montgomery, Stuart Spencer, Bruce Fry, Joe Maley, Bruce Fry, Mike McCay, Tim Holdener, Ryan Sherman, and Chad Joseph.

Of course, there are other Lodi Zinfandel growths with unique profiles that have become fairly easy to identify (at least to the cognoscente), but the aforementioned are undoubtedly the best known — at least for now.

And as more and more small, handcraft, minimal intervention wineries produce Carignans from vineyards like Jessie’s Grove‘s 1900 Block (also called Spenker Ranch) and the Shinn family’s Mule Plane Vineyard (planted in the 1920s), we are beginning to get a very good feel for these growths’ terroir-related identities. Hopefully, this will serve as examples that will lead to increased valuation of other old vine Lodi plantings that are lesser-known and still largely unappreciated — lest they be ignominiously torn out from the ground for lack of perceived marketability.

The direct impact of terroir on Bokisch Vineyards’ Albariño plantings: on left, Las Cerezas Vineyard (plump cluster grown in rich sandy loam soil) vs. on right, Terra Alta Vineyard (shallower rocky clay soil, producing lighter canopy resulting in smaller, more sun-influenced clusters).

But identifiable terroirs in Lodi are not just about old or ancient vines. Just over the past 20 years, Bokisch Vineyards has forged a strong track record with its Albariño and Tempranillo, bottled as vineyard-designate wines from vineyards such as Las Cerezas in Lodi’s Mokelumne River AVA, Liberty Oaks Vineyard in Jahant-Lodi, and Terra Alta Vineyard in Clements Hills-Lodi. Tasting through the sensory profiles derived directly from these distinctive vineyards and sub-appellations is a fascinating exercise in terroir discoveries (see Bokisch Vineyards demonstrates the impact of terroir on grapes).

Our next blog post: The influence of Lodi Native and list of vineyard-designate wines in Lodi

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine and crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.