MAY 11, 2020. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

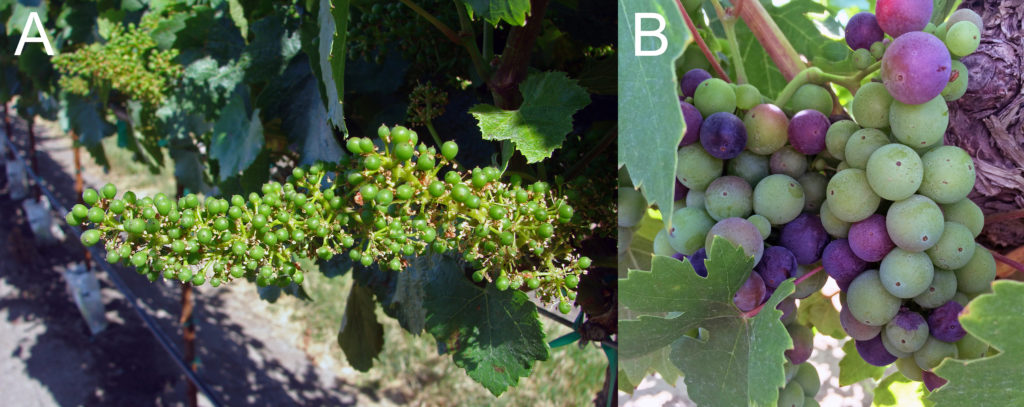

The post bloom period begins as the fruit sets and it ends as the berries begin to change color (Figure 1). During this time, vine growth and development lay the foundation for ripening and grape quality. Concomitantly, there are opportunities to affect fruit yield and fruit production efficiency. For these reasons, post bloom is a pivotal time in vineyard management.

Figure 1. The post bloom period begins with fruit set (A) and ends with the onset of fruit coloration (B). (Progressive Viticulture©)

Normal Post Bloom Events

As newly set fruit grow, they increasingly draw upon the supply of internal grapevine resources. At the same time, if all is working well in the vineyard, soil moisture will have been depleted to such an extent that vines come under moderate water stress. These two post bloom developments, increasing internal competition for resources and a limiting supply of moisture, cause shoot growth to slow and eventually cease (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A senescing shoot tip and very short apical internodes indicate shoot growth is nearly arrested. (Progressive Viticulture©)

Also, if all is working well, most shoots have 14 to 20 leaves when they stop growing. In the vast majority of situations in California, the photosynthetic capacity with this leaf count is sufficient to ripen two clusters per shoot, ripen stems, and store carbohydrates in woody tissues for use early in the next growing season. As such, vines have an effective balance between leaves and fruit growth.

Growth balance is an essential ingredient for optimum winegrape quality and fruit production efficiency. The moderate water stress that contributed to arresting shoot growth is another.

A Call to Action

If shoot growth slows before producing sufficient leaves, it is imperative for the vineyard manager to take immediate actions to stimulate renewed shoot growth and promote complete canopy development. Failure to do so results in overcropping (Figure 3).

Figure 3. This Cabernet Sauvignon vine with too few leaves relative to berries is overcropped. (Progressive Viticulture©)

In many cases, simply applying water is enough to renew shoot elongation. In others, fertilizer is required and frequently, a two-step fertigation approach works best.

First, apply a fertilizer designed to promote root activity, including mineral nutrient uptake from the soil and hormone synthesis and translocation to shoots. These fertilizers typically contain a small quantity of ammonium-nitrogen, abundant phosphorus, and other stimulatory compounds, such as organic acids. Examples include Mar Vista Foundation MVR, Redox Rootex, Actagro Structure, and AgroLiquid PrG.

Second, apply a fast acting nitrogen fertilizer to invigorate shoot growth and promote continued leaf production. Calcium nitrate (CN-9) is the best option for this purpose because roots readily take it up and it easily moves to shoots.

Failure of applied water and fertilizers to prompt shoot growth indicates other factors are limiting. They may be other mineral nutrients, such as boron or manganese involved in nitrogen metabolism. Underperforming roots due to pests, diseases, and past stresses are also capable of restricting shoot growth responses to applied resources. More often, carbohydrate reserves in woody vine tissues limited from stresses during the previous season restrict shoot growth. Regardless of the constraint, if sufficient leaves cannot be grown within a few weeks of bloom, remove clusters to avoid overcropping and vine decline.

The Opposite Condition

Under some circumstances, an abundance of soil resources sustain shoot growth well beyond 20 leaves per shoot (Figure 4). Too much shoot growth, like too little shoot growth, demands a vineyard manager’s immediate attention.

Figure 4. Merlot canopies continue to develop in excess after they were hedged. (Progressive Viticulture©)

The viticultural risks associated with copious foliage are mostly associated with restricted air movement within the canopy interior and excessive leaf and fruit shading. They include increased fungal disease, poor coverage of foliar-applied chemicals, strong vegetative characters in the fruit, decreased cane winter hardiness, and low fruitfulness during the following year. To remedy this undercropped situation, withhold water to arrest shoot growth and after shoot growth is under control, hedge canopies to impose growth balance.

Fine Tuning the Foundation for Ripening and Grape Quality

As mentioned above, two ingredients for optimized winegrape quality and fruit production efficiency are moderate water stress and a favorable balance between leaves and fruit after fruit set. The third is fruit exposure to dappled sunlight. Such exposure also facilitates airflow and applied chemical coverage in the fruit zone.

For some vineyards and varieties, prebloom shoot thinning to 6 to 7 per foot of cordon provides adequate fruit zone exposure. Others, however, require post bloom basal leaf and/or lateral shoot removal to increase fruit zone exposure. The optimum timing of leaf and lateral shoot removal is immediately after the fruit has set. Earlier removal induces flower shatter and yield loss, and later removal shortens the time berries have to acclimate to increased sunlight, which increases the risk of sun damage.

Advancing Fruit Yield

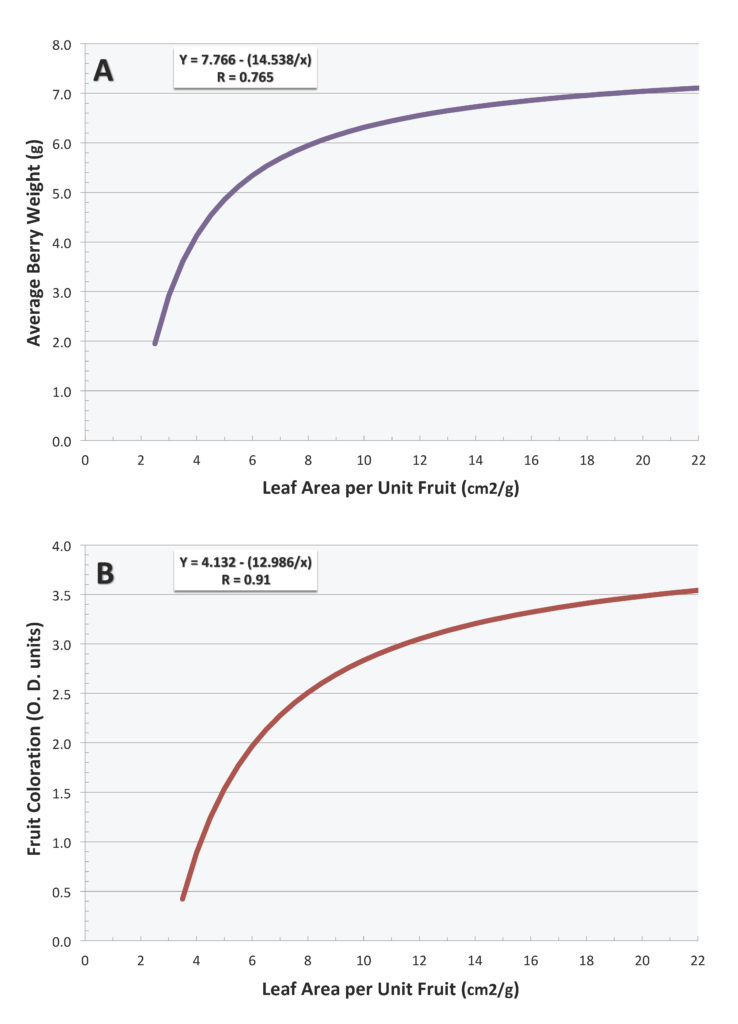

Figure 5. Berry weight (A) and fruit color (B) increase with more leaf area relative to crop (B). (Kliewer, WM; Weaver, RJ)

Vineyard managers can influence berry size and thereby, harvested fruit yield with their actions during the post bloom period. The size of young berries increase mainly due to cell division and typically, 65% to 75% of their final size is determined before the onset of ripening.

Cell division, the final number of berry cells, and berry size are limited in proportion to the intensity of post bloom grapevine water stress. Accordingly, maintaining vines on the wetter side of moderate water stress (leaf water potential ≈ -10 bars) promotes normal sized berries and consistent yields.

Yields may be further enhanced through fertilizer nitrogen applications, but do not make such applications if shoot growth is out of control and canopy development is excessive. Post bloom cluster thinning reduces completion among berries for internal vine resources and as a result, increases berry size, but at the same time, decreases yield.

Many winemakers associate small berries with optimum winegrape quality and may encourage you to manage your vineyard accordingly after bloom. Research results do not support this notion. Rather, published data indicate grape color increases with berry size when clusters are thinned early (Figure 5).

Late Post Bloom Disease Control Concerns

Within a few weeks after bloom, regardless of vine water stress level, the berries of many varieties will swell large enough to touch their neighbors. This developmental stage is known both as the beginning of berry touch and the beginning of bunch closure (Eichhorn-Lorenz stage 33).

The beginning of berry touch effectively ends the window of opportunity for spray penetration into the interiors of clusters. Therefore, fungicide applications to control bunch rot inoculum on dead flower parts adhering to clusters must occur before this developmental stage. For powdery mildew control, continue fungicide treatments throughout the post bloom period because the juvenile tissues of green berries are susceptible to this disease.

The End of Post Bloom

The post bloom period ends with the onset of ripening or as it is commonly known, veraison. It is visibly evident as color changes in the fruit and an invisible influx of sugar into berries precedes it. In some vineyards, a low rate application of readily available potassium at the onset of veraison can enhance the sugar influx and fruit coloration.

If everything is working well in the vineyard, main stems will have turned yellow or woody by veraison. To ascertain the nutritional status of your vines and the need for fertilizer applications to support the fruit and cane wood ripening that lies ahead, collect leaf blade tissue samples during veraison and submit them for analysis.

In Summary

Post bloom is a period of transition for grapevines in which they shift their energies from vegetative to reproductive growth and development. During this time, the foundation for ripening is finished and some factors effecting sensory attributes in berries are determined. For this reason, it is a time for vineyard managers to set the stage for optimum winegrape quality, fruit yield, and production efficiency through actions affecting vineyard water, nutrients, canopies, and crops.

This a modified version of an article published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services May, 2012 newsletter. The article was updated for this blog post on May 11, 2020.

Further Reading

Bernizzoni, F; Gatti, M; Civardi, S; Poni, S. Long-term performance of Barbera grown under different training systems and within-row vine spacings. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 60, 339-348. 2009.

Bettiga, LJ (Ed.). Grape pest management. 3rd Ed. University of California Agricultural and Natural Resources, Oakland, CA. Publication 3343. Pp. 120-125. 2013.

Grant, S. Five-step irrigation schedule: promoting fruit quality and vine health. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 21(1): 46-52 and 75. May/June 2000.

Grant, S. Balanced soil fertility management in wine grape vineyards. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 24 (1): 7-24. May/June 2002.

Grant, S. Fertilizer efficiency for wine grape vineyards. Practical Winery and Vineyard 28 (1): 35-41. March/April 2006.

Grant, S. Regulated deficit irrigation, parts I and II. Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (www.lodigrowers.com). July 18 and August 04, 2014.

Grant, S. To hedge or not to hedge? Lodi Winegrape Commission Coffee Shop. (www.lodigrowers.com). June 06, 2017.

Keller, M. The science of grapevines. Academic Press, Burlington, MA. 2010

Kliewer, MK; Weaver, RJ. Effects of crop load and leaf area on growth, composition, and coloration of ‘Tokay’ grapes. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 22, 172-177. 1971.

Matthews, MA. Terroir and other myths of winegrowing. University of California Press, Oakland. 2015.

Mullins, MG; Bouquet, A; Williams, LE. Biology of the grapevine. Cambridge University Press. 1992.

Ohmart, CP, Storm, CP, Matthiasson, SK (Eds.). Lodi Winegrower’s Workbook, 2nd Ed. Lodi Winegrape Commission. pp. 187-267. 2008.

Smart, R: Robinson, M. Sunlight into wine: A Handbook for Winegrape Canopy Management. Winetitles, Adelaide. 1991.

Wilcox, WF; Gubler, WD; Uyemoto, JK (ed.). Compendium of Grape Diseases. 2nd ed. APS Press, St. Paul, MN. pp. 33-39. 2015.

Winkler, AJ; Cook, JA; Kliewer, MK; Lider, LA. General Viticulture. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1974.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.