MONDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2021. BY STAN GRANT, VITICULTURIST.

Pinot noir is the grape of Burgundy, which is among the most revered red wines in the world. Pinot noir is also a very old grape variety. In fact, Roman writings suggest Pinot noir was already cultivated in Gaul (western Europe) in the first century AD. Today, Pinot noir is present in nearly all counties that produce winegrapes.

Clonal Variations in Pinot noir

During it’s long existence, Pinot noir has had ample opportunity for mutations leading to clonal variations. Some experts suspect ancient grape growers repeatedly collected dark fruited Pinot-like vines from wild populations for cultivation, which compounded the number of variations within the variety. Due to these factors and perhaps, a tendency for genetic instability, Pinot noir has more clones than any other winegrape cultivar. At this time, Foundation Plant Services in Davis, CA, has about 95 unique Pinot noir clones in its collection for the California wine industry. The viticultural and wine characteristics of most of these clones under California conditions are unknown.

Pinot noir clones differ in growth habit, leaf shape, cluster size, and berry size, but not significantly in growth vigor. Variations among Pinot noir clones, more or less, fit into four groups. They are the high quality (Pinot fin), loose clustered (Mariafeld), upright shoots (Pinot droit or, in California, Gamay Beaujolais), and fruitful or fertile (Pinot fructifer) clone groups.

In California, fruit from clones within each of these groups have produced excellent quality wines. Many newer California Pinot noir vineyards incorporate Pinot fin clones, but loose clustered clones (e.g. Pn-23) and upright clones (e.g. Pn-18) are also common. Among Pinot fin clones, California selections (2A, 4, 10, and 29) generally produce higher fruit yields and greater pruning weights than the Dijon clones (113, 114, and 115).

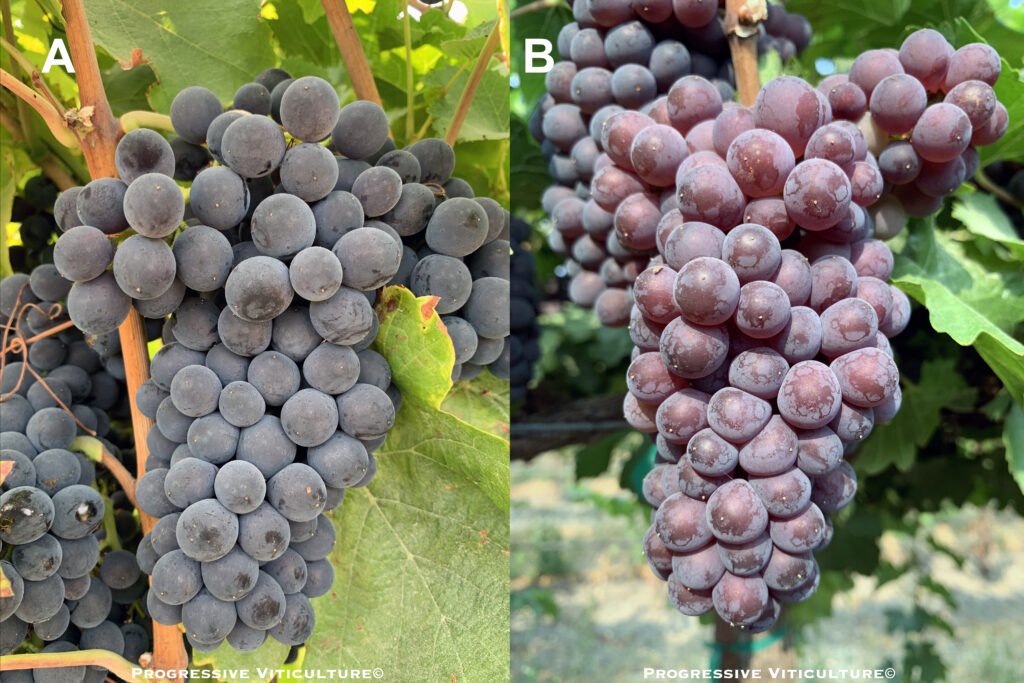

Figure 1. Pinot gris (B) is a color mutant of Pinot noir (A) in which the lost capacity for color production has been partially restored. (Photo source: Progressive Viticulture©)

The Colors of Pinot

The red pigment molecules (anthocyanins) in the skins of Pinot noir berries are somewhat unique among red winegrape varieties. They are composed of a relatively high percentage of molecules with a malvidin base and they have no organic acids esterified to their attached glucose (i.e. they are not acylated). The comparative simplicity of these molecules may contribute to the early coloration and ripening of Pinot noir fruit.

Pinot blanc and Pinot gris are fruit color mutants of Pinot noir (Figure 1). Both are used to produce white wines. Pinot Meunier is a red-fruited, slightly more vigorous variant of Pinot noir that is used in sparkling wine production to a limited degree in California and to a large extent in France. In some instances, red berry color in Pinot varieties is not entirely stable (Figure 2).

These varieties – Pinot noir, Pinot gris, Pinot blanc, and Pinot Meunier – constitute the Pinot family. In addition to color, they differ from one another in the acidity, aroma, and flavor characteristics of their fruit and wines. All emerge from dormancy early and their fruit ripens early compared to many other winegrape varieties. Both Pinot gris and Pinot blanc are significant varieties in Italy, where they are known as Pinot grigio and Pinot bianco, respectively.

Figure 2. A mutant shoot or sport bearing white berries (lower right) on a Pinot gris-146 grapevine in Clarksburg, California. (Photo source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Viticultural Characteristics of Pinot

Pinot varieties grow and develop somewhat differently than other common winegrape varieties. As a consequence, a winegrower new to them may need to slightly alter his or her approach.

Compared to other common varieties, the shoots of Pinot varieties grow slowly and their canopies develop late, often reaching full canopy (14 to 20 nodes per shoot) weeks after fruit set (Figure 3). Due to this trait, growing Pinot shoots may appear somewhat unresponsive to applied water and nitrogen. At the same time, shortages of such resources ultimately restrict canopy development and limit ripening capacity. Therefore, it is often prudent to slightly over resource rather than under resource vines in the Pinot family early in the growing season.

Figure 3. Pinot canopies develop more slowly than most other varieties. These Pinot gris vines have completely developed mid season canopies with many well exposed leaves in balance with the quantity of fruit. (Photo source: Progressive Viticulture©)

A side effect of slow shoot growth, or perhaps a cause of it, is weaker than usual apical dominance in Pinot varieties. Apical dominance is the phenomenon in which hormones produced in shoot tips suppress the growth of organs below them as they move downward (lodigrowers.com/using-competition-to-best-advantage-in-vineyard-management/). Perhaps the most visible evidence of relatively weak apical dominance is the strong tendency of Pinot varieties to produce suckers on the bases of their trunks (Figure 4). Another is the apparent responsiveness of Pinot varieties to rootstock influences, which provides vineyard managers some influence over vine characteristics.

The comparative low growth vigor of Pinot varieties makes them prone to overcropping. Overcropping, of course, results in delayed fruit maturation and potentially, vine decline. In addition, overcropping greatly diminishes fruit color, aroma, and flavor.

Figure 4. Pinot gris vines, like those of other Pinot varieties, tend to produce suckers on the bases of their trunks. (Photo source: Progressive Viticulture©)

Designing and managing Pinot vineyards for a high percentage of sun exposed leaves, prompt canopy development, and moderate crop loads avoids or at least, minimizes overcropping (Figure 3). In the California interior, the designs for Pinot noir vineyards commonly target about 20 pounds of fruit per vine, while coastal vineyard designs target less. Correspondingly, economic sustainable yields on a per acre basis often require high vine densities and horizontally divided trellises. Even with these measures, cluster thinning to achieve a favorable balance between fruit and exposed leaf area is sometimes needed.

In addition to crop stress, Pinot fruit ripening appears fairly sensitive to environmental stresses, including severe water stress and heat stress. Again, it is better to slightly overdo efforts to avoid or minimize such stresses than to underdo them. In this regard, irrigate to keep Pinot varieties on the wetter side of moderate water stress (i.e. leaf water potential between -10 and -12 bars) during ripening. Also, suspend regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) schedules and liberally irrigate before, during, and for a couple of days after periods of triple digit maximum daily temperatures.

According to published reports, Pinot noir and Pinot gris are highly susceptible to powdery mildew, but Pinot blanc and Pinot Meunier are only moderately susceptible. The thin berry skins and dense clusters typical of Pinot varieties predispose them to bunch rot, but there are differences among clones in susceptibility (Figure 5). Finally, Pinot gris and Pinot Meunier are highly susceptible to wood diseases. Pinot blanc, however, is moderately susceptible to wood diseases and the relative susceptibility of Pinot noir is unreported.

Figure 5. A rotting Pinot noir cluster. (Photo source: Progressive Viticulture©)

In Closing

Pinot varieties have some traits that make them unique among winegrape varieties, while at the same time there is great variability within the Pinot family. They can be challenging to grow and often demand the best efforts of a vineyard manager.

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services October 2014 newsletter and was updated for this blog post. All material posted on this blog and website serves an educational purpose only.

Featured image of Pinot noir grapes in Mokelumne Glen Vineyard by Randy Caparoso.

Further Reading

Anonymous. Botrytis Bunch Rot (Botrytis cinerea). British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture. http://www.agf.gov.bc.ca/cropprot/grapeipm/bunchrot.htm

Anonymous. Chapter 8. Pest Management. In North Carolina Winegrape Grower’s Guide. North Carolina State University. http://cals.ncsu.edu/hort_sci/extension/wine_grape.php

Bavaresco, L, Fraschini, P, and Perino, A. Effect of rootstock on the occurrence of lime-induced chlorosis or potted Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Pinot blanc’. Plant and Soil. 157, 305-311. 1993.

Becker, N, Thoma, K, and Zimmerman, H. Performance of Pinot noir clones. p. 282-284. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. 1988. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Bernard, R, and Leguay, M. Clonal variability in Burgundy and its potential adaptation under cool climates. p. 63-74. In D.A. Heatherbell, P.B. Lombard, R.W. Bodyfelt, and S.F. Price (eds.) Proc Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vit. Enol. Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Publication #7628. 1984.

Bernard, R, and Leguay, M. Pinot noir in cooler climates. Wines and Vines. p. 47-49. Feb. 1986.

Candolfi-Vasconcelo, M.C., Koblet, W, Howell, G.S., and Zweifel, W. Influence of defoliation, rootstock, training system, and leaf position on gas exchange of Pinot noir grapevines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 45, 173-180. 1994.

Candolfi-Vasconcelos, M.C., and Castagloli, S. Performance of Pinot noir and Chardonnay clones. Oregon State University. Unpublished report.

Cirami, R.M., McCarthy, M.G., and Furkaliev, D.G. Pinot noir – clones suitable for champagne or red wine styles. Australian Grapegrower and Winemaker. p. 16-17. Nov. 1984.

Coldwell, J. A concise guide to wine grape clones for professionals. John Caldwell Viticultural Service. Napa, California. Undated.

Coombe, B.G., Webb, A.D., and Williams, P.J. Anthocyanins. p. 25-26. In J. Robinson (ed.). Oxford companion to wine. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1999.

Doster, M.A., and Schnathorst, W.C. Comparative susceptibility of various grapevine cultivars to the powdery mildew fungus Uncinula necator. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 36, 101-104. 1985.

Drouhin, R.J. Burgundy experiences with Pinot noir and Chardonnay. p. 270-272. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Ewart, A.J.W., and Sitters, J.H. Wine assessment of Pinot noir, Chardonnay, and Riesling clones. p. 201-205. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Ewart, A.J.W., and Sitters, J.H. Latest results on Pinot noir clones for dry red wine. Australian Grapegrower and Winemaker. p. 115-117. Apr. 1989.

Franson, P. Gallo speaks. Wine Business Monthly. p. 19-26. Aug. 2000.

Foundation Plant Material Services. FPMS registered, provisional, non-registered and quarantine grape selections. Univ. Calif., Davis. Aug. 1, 2000.

Gubler, W.D., and Leavitt, G.M. Eutypa dieback of grapevines. p. 71-75. In: Grape Pest Management. Flaherty, D.L., Christensen, L.P., Lanini, W.T., Marois, J.J., Phillips, P.A., and Wilson, L.T. (eds.). Univ. Calif. Div. Agric. Sci. Oakland. 1992.

Heald, E, and Heald, R. Pinot noir – varietal review. Practical Winery and Vineyard. p. 50-53. Mar./Apr. 1995.

Hock, S. Clonal selections: obstacles and opportunities with Pinot Noir. Practical Winery and Vineyard. p. 37-42. May/June 1989.

Keller, M. The science of grapevines. Academic Press, Burlington, MA. 2010.

Kerridge, G, and Antcliff, A. Wine grape varieties. CSIRO Publishing. 1999.

Koblet, W, Candolfi-Vasconcelos, C.M., Zweifel, W, and Howell, G.S. Influence of leaf removal, rootstock and training system on yield and fruit composition of Pinot noir grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic. 45. 181-187. 1994.

Leavitt, GM. Canker diseases of grapevines. U. C. Coop. Ext, Madera. Undated report.

Marois, J.J., Bledsoe, A.M., and Bettiga, L.J. Botrytis bunch rot and Miscellaneous secondary invaders and sour rot. In Flaherty, D.L., et. al. (ed.). Grape pest management. Univ. Calif. Div. Agric. Nat. Res. Oakland, Calif. 1992.

McCarthy, M.G. Clonal comparisons with Pinot noir, Chardonnay, and Riesling clones. p. 285-286. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Mercado-Martin, G.I., Wolpert, J.A., and Smith, R.J. Viticultural evaluation of eleven clones and two field selections of Pinot noir grown for production of sparkling wine in Los Caneros, California. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 57, 371-376. 2006.

Mochizuki, M, Donovan, L, Aiken, J, and Walsh, M. Clonal effects on Pinot noir yield and wine quality parameters. p. 129-132. In J.M. Ranz, J.A. Wolpert, E. Weber, M.A. Walker, and D. Roberts (eds.) Int. Symp. Clonal Selection. Amer. Soc. Enol. Vitic. 1995.

Pool, R.M., Henick-Kling, T, Howard, G.E., Gavitt, B.K., and Johnson, T.J. Pinot noir clonal research in New York. p. 45-51. In J.M. Ranz, J.A. Wolpert, E. Weber, M.A. Walker, and D. Roberts (eds.) Int. Symp. Clonal Selection. Amer. Soc. Enol. Vitic. 1995.

Price, S.F., Lombard, F.B., and Watson, B.T. Pinot noir clones and their effects on cluster morphology and grape composition. p. 279-281. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Price, S.F., and Watson, B.T. Preliminary results form an Oregon Pinot noir clonal trial. p. 40-44. In J.M. Ranz, J.A. Wolpert, E. Weber, M.A. Walker, and D. Roberts (eds.) Int. Symp. Clonal Selection. Amer. Soc. Enol. Vitic. 1995.

Robinson, J. Wines, grapes, and wines: the wine drinkers guide to grape varieties. Reed International Books, London, 1986.

Rossmann, S, Richter, R, Sun, H, Schneeberger, K, Topfer, R, Zyprian, E, and Theres, K. Mutations in the miR396 binding site of the growth- regulating factor gene VvGRF4 modulate inflorescence architecture in grapevine. The Plant Journal. 101, 1234-1248. 2019.

Roy, R.A., and Ramming, D.W. Varietal resistance of grape to the powdery mildew fungus, Uncinula necator. Fruit Varieties Journal. 44:149-155. 1990.

Singleton, V.L. Grape and wine phenolics: background and prospects. In AD Webb (ed.). Grape and wine centennial symposium proceedings. Univ. Calif., Davis. 1980.

Smart, R. Pinot noir – the ultimate viticultural challenge? Australian Grapegrower and Winemaker. p. 77-85. Apr. 1992.

Smith, R.J. Pinot noir. p. 107-111. In Bettiga, L.J., Christensen, L.P., Dokoozlian, N.K., Golino, D.A., McGourty, G, Smith, R.J., Verdegaal, P.S., Walker, M.A., Wolpert, J.A., and Weber, E (eds.) Wine grape varieties in California. Univ. Calif. Agric. Natural Resources Pub. 3419. 2003.

Smith, R.J. Pinot blanc. p. 113. In Bettiga, L.J., Christensen, L.P., Dokoozlian, N.K., Golino, D.A., McGourty, G, Smith, R.J., Verdegaal, P.S., Walker, M.A., Wolpert, J.A., and Weber, E (eds.) Wine grape varieties in California. Univ. Calif. Agric. Natural Resources Pub. 3419. 2003.

Smith, R.J. Pinot gris. p. 115. In Bettiga, L.J., Christensen, L.P., Dokoozlian, N.K., Golino, D.A., McGourty, G, Smith, R.J., Verdegaal, P.S., Walker, M.A., Wolpert, J.A., and Weber, E (eds.) Wine grape varieties in California. Univ. Calif. Agric. Natural Resources Pub. 3419. 2003.

Smith, R.J. Pinot Meunier. p. 117. In Bettiga, L.J., Christensen, L.P., Dokoozlian, N.K., Golino, D.A., McGourty, G, Smith, R.J., Verdegaal, P.S., Walker, M.A., Wolpert, J.A., and Weber, E (eds.) Wine grape varieties in California. Univ. Calif. Agric. Natural Resources Pub. 3419. 2003.

Vezzulli, S, Leonardelli, L, Malossini, U, Stefanini, M, Velasco, R, and Moser, C. Pinot blanc and Pinot gris arose as independent somatic mutations of Pinot noir. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 6359-6369. 2012.

Walker, L. Send in the clones. Wines and Vines. p. 16-19. Dec. 1994.

Watson, B.T., Lombard, L.B., Price, S.F., McDaniel, M, and Heatherbell, D. Evaluation of Pinot noir clones in Oregon. p. 276-278. In R.E. Smart, R. Thornton, S.B. Rodriquez, and J.E. Young (eds.) Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. Cool Climate Vitic. Oenol. N.Z. Soc. Vitic. Oenol. 1988.

Watson-Gaff, P. Pinot Noir: color extraction and stability. Practical Winery and Vineyard. p. 73-79. May/June 1988.

Whiting, J.R., and Hardie, W.J. Comparison of selections of Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot noir in Great Western, Victoria. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 30:281-285. 1990.

Wolpert, J. An overview of Pinot noir clones tested at UC-Davis. Vineyard and Winery Management. p. 18-21. July/Aug. 1995.

Winkler, A.J., Kliewer, W.M., Cook, J.A., and Lider, L.A. General viticulture. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1974.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe.”

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

For more information on the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Program, visit lodigrowers.com/standards or lodirules.org.