Deficit irrigation refers to the practice of applying less than the full amount of water a vineyard can use. The objective of deficit irrigation is to induce and sustain moderate water stress that arrests shoot growth and limits fruit growth without impacting foliage health and sugar accumulation. This is possible because shoot growth and berry growth are more sensitive to water stress than sugar accumulation. Deficit irrigation reduces irrigation costs and bunch rot, but also improves fruit quality through increased fruit acidity, lowered pH, and increased phenolics (color, aroma, flavor, and astringency). Many wineries promote deficit irrigation because the fruit quality benefits translate into higher quality wines that effectively compete in the wine market.

Deficit irrigation refers to the practice of applying less than the full amount of water a vineyard can use. The objective of deficit irrigation is to induce and sustain moderate water stress that arrests shoot growth and limits fruit growth without impacting foliage health and sugar accumulation. This is possible because shoot growth and berry growth are more sensitive to water stress than sugar accumulation. Deficit irrigation reduces irrigation costs and bunch rot, but also improves fruit quality through increased fruit acidity, lowered pH, and increased phenolics (color, aroma, flavor, and astringency). Many wineries promote deficit irrigation because the fruit quality benefits translate into higher quality wines that effectively compete in the wine market.

__________________________________________________________________________________

This is the first of a two part series on regulated deficit irrigation by Stan Grant. Part II will be posted on August 4th.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Successful deficit irrigation has a few requirements. First, effective deficit irrigation requires sustained moderate water stress while avoiding severe water stress, which is detrimental to fruit quality and vine health. The Australians who pioneered the technique refer to it is as regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) to emphasize the importance of regulating the water stress with the moderate range.

Successful RDI also requires that early in the season, prior to imposing water stress, vines have access to sufficient soil moisture to produce fully developed canopies (14 to 20 nodes per shoot)(fig 1). In addition, it requires that after harvest until the first frost, vines have access to sufficient soil moisture to relieve stress and maintain healthy leaves, which is critical for producing and storing carbohydrates for use early in the next growing season. Therefore, a sustainable RDI strategy involves minimum water stress prior to fruit set, moderate water stress from fruit set to harvest, and minimum water stress following harvest.

__________________________________________________________________________________

A version of this article was originally published in the Mid Valley Agricultural Services’ May 2002 newsletter.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Normally, no early season irrigations are required to grow full canopies in vineyards with small vines or low vine densities and soils with large moisture holding capacities. In contrast, vineyards with large vines or high vine densities and soils with low moisture holding capacities often will not reach full canopies without early season irrigations. For example, early season irrigations are rarely necessary for small head trained vines on deep Tokay sand loam near Lodi, but they are common for quadrilateral trained vines on Redding gravelly loam in the Clements area. The need for early season irrigations can be determined from vine appearance, pressure bomb readings, or soil moisture measurements.

During the growing season, successful RDI implementation requires monitoring of the moisture continuum that extends from the soil either directly to the atmosphere or through the vines to the atmosphere (fig 2). Of course, within the continuum our primary focus is the vines. Their condition and appearance at any particular time during the growing season relative to the state we expect or want is the primary consideration for our irrigation scheduling decisions.

Early in the season shoots should have a moderate growth rate and leaves should be normal in size. After reaching full canopy, suspend irrigations or continue to withhold them to arrest shoot growth, which is evident in pale shoot tips, short internodes near the tips, obscuring of the shoot tip by apical leaves, and possibly, slight tendril and petiole wilting during the warmest part of the day (fig 3).

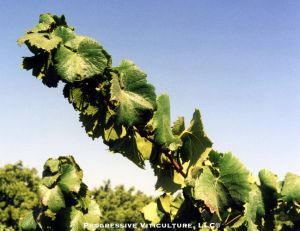

Once shoot growth has been arrested, RDI is practiced to sustain foliage without renewed shoot growth (fig 4). Basal leaf yellowing or scorching indicate severe water stress and the need for increased irrigation. Before such leaf damage is readily apparent, leaves may appear slightly wilted and exposed leaf tissues may be warm and appear faded.

Development of full canopies, arresting of shoot growth, and imposition of moderate water stress should occur shortly after bloom to achieve the maximum fruit quality benefits from RDI. Later timings will still render beneficial effects, but they are somewhat diminished.

In the next posting, we will discuss the other components of the soil-vine-atmosphere continuum and irrigation scheduling after shoot growth has been arrested.

Figure 4: Mid season healthy grapevine foliage maintained under moderate water stress. Photo: Progressive Viticulture©

Further Reading

- Goldhammer, DA; Snyder, RL. Irrigation scheduling: a guide for efficient on-farm water management. University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 21454. 1989.

- Grant, S. Five-step irrigation schedule: promoting fruit quality and vine health. Practical Winery and Vineyard. 21(1): 46-52 and 75. May/June 2000.

- Hanson, B; Orloff, S; Sanden, B. Monitoring soil moisture for irrigation water management. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 21635. 2007.

- Hardie, W. J., and J. A. Considine. Response of grapes to water-deficit stress in particular stages of development. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 27, 55-61. 1976.

- Matthews, M. A., R. Ishii, M. M. Anderson, and M. O’Mahony. Dependence of wine sensory attributes on vine water status. J. Sci. Food Agric. 51: 321-335 (1990).

- Matthews, M. A., and M. M. Anderson. Fruit ripening in Vitis vinifera L.: responses to seasonal water deficits. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 39, 313-320. 1988.

- Matthews, M. A. and M. M. Anderson. Reproductive development in grape (Vitis vinifera L.): responses to seasonal water deficit. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 40: 52-60. 1989.

- Prichard, TL; Hanson B; Schwankl, L; Verdegaal, P; Smith, R. Deficit irrigation of quality winegrapes using micro-irrigation techniques. University of California Cooperative Extension, Department of Land, Air, Water Resources, University of California, Davis. 2004.

- Prichard, T; Storm, CP; Ohmart, CP. Chapter 5, Water Management. In: Lodi Winegrower’s Workbook, 2nd Ed. Ohmart, CP, Storm, CP, Matthiasson, SK (Eds.). Lodi Winegrape Commission. pp. 142-186. 2008.

- Schwankl, L; Hanson, B; Prichard, T. Micro-irrigation of trees and vines: a handbook for water managers. University of California Irrigation Program, University of California, Davis. 1995.

© Progressive Viticulture