Many felt like mildew was raining down last year and nothing they did would slow it down. You might have heard of the results from our American Vineyard Foundation (AVF) funded research on DMI (FRAC 3) and strobilurin (FRAC 11) fungicide resistant powdery mildew and think/hope that this was the cause of all your problems.

Many felt like mildew was raining down last year and nothing they did would slow it down. You might have heard of the results from our American Vineyard Foundation (AVF) funded research on DMI (FRAC 3) and strobilurin (FRAC 11) fungicide resistant powdery mildew and think/hope that this was the cause of all your problems.

Well, that is probably not accurate. In over 30 years of research, I have found nothing that easily explained it. Managing grape powdery mildew is an intricate dance with mother nature, and she likes to change the steps without warning. Thus, it is very easy to get out of sync with her. Last year, she changed a lot of steps.

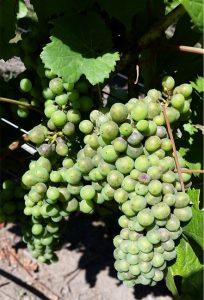

Powdery Mildew that got out of control.

Strike one. There were massive amounts of water in the ground – about double normal – but the air and ground temperatures were normal, so bud break rolled in at its normal time. Unfortunately, your tractors couldn’t. The rains in March made sure the mildew epidemic was starting early while your tractors sat idle waiting for the ground to dry. Then the temperatures and humidity combined with reduced solar radiation to make for rapid shoot growth and massive succulent leaves – the perfect environment for mildew infection.

While we are here, did you calibrate your sprayer/duster over the winter? Did you check to see if you are getting the coverage needed? If you didn’t, you’re facing a lefty with a wicked fastball. A poorly calibrated sprayer can cause too little fungicide to land on the plant or excessive spray that often does not stay on the plant. Either way, money and time are wasted and often disease management is compromised.

Spray calibration and coverage (deposition) are not the same thing. Calibration is measuring the volume of material leaving the sprayer/duster. This knowledge allows to you better guess how much will land on your target. Assessing coverage is difficult work since you really can’t calculate it – you have to measure it. The easiest and most practical method is using kaolin clay or micronized sulfur in your sprayer and examining the pattern on leaves and clusters. You can use the “PMapp” app to help train your eye to judge coverage on clusters. Next, the easiest method is placing water sensitive paper on the back side of leaves and clusters (e.g. the hardest area to reach) and using the SnapCard app (Android, Apple) to measure coverage. Andrew Landers has a website and a great book called “Effective vineyard spraying, 2nd edition” that has many more details on measuring calibration and coverage.

The most common coverage issues I have observed over the years are:

1) trunk suckers not getting sprayed;

2) Nozzles not pointing at the canopy – either missing parts of the canopy or spraying at the sky or ground;

3) driving too fast, causing spray to not penetrate the canopy – it takes time to create the turbulence needed to make leaves move out of the way and allow spray into the interior of the canopy.

Strike two. Shoot growth was fast which means application intervals needed to be more frequent than most years. Only a few fungicides move very far from the point of application and those that do move can be quickly diluted to ineffective concentrations with plant growth. Effective application intervals match plant growth, not a calendar. The bigger the leaf, the harder it is to move the leaf with air and the bigger the canopy, the more likely leaves will overlap with other leaves to form a wall that prevents fungicide from penetrating the canopy. The other issue with big canopies is that they trap humidity and reduce light penetration to make the environment more suitable for mildew development. This often leads to the disease developing right in the cluster zone.

Did you adjust application volume up, adjust the air velocity, and drive slower with the change in canopy size?

I heard some say that the Gubler/Thomas model did not indicate the need to spray. A common misconception about the G/T index is that it indicates spray/don’t spray. That is not what it was designed to do. The index hints at the application interval you should be using based on temperature. Low index = longest label intervals. High index= shortest label intervals. However, you still need to consider how much disease is in the canopy and how much growth has occurred when deciding the application interval. As good as the index is for many regions, I have found over the last twenty years that it tends to underestimate risk of infection in overcast environments and inside dense canopies; especially if there is a lot of lateral growth. Regardless of the index, you still need to keep tissue protected and keep up with plant growth. The weather did not make that easy this year.

Targeting applications of mobile chemistries at 50% bloom could go a long way in helping keep the fruit clean. Our research funded by the Oregon Wine Board examining fungicide timing is summarized here. Of course, these timings require a good management program before and after flowering and assume that the fungicide reaches the fruit zone. Leaf pulling anyone? It is something to think about when vigor can’t be managed with irrigation.

Fungicide selection is always a difficult topic because of the multitude of factors that go into what is chosen. We could all argue for days about what is the right rotation and when to use what products. There is not a correct answer because of the diversity in how vineyards are designed, managed and their microclimates. Thus, selection comes down to understanding products and their limitations. For example, I keep hearing folks talk about eradicants. In my opinion, there is no such thing. I have not seen any data that convinces me that any currently registered product is an eradicant. I prefer to use the term “knock-down.” These products (e.g. oils) can slow pathogen growth and sporulation for a period of time and sometimes result in the colony no longer producing spores. However, I think more often than not the colony recovers and sporulates again, but for a shorter period of time. This is largely because the plants’ natural defenses catch up with the pathogens’ growth, which has been slowed by these products. Do not get me wrong; “knock-down” products have their place in a management program, but they are not a magic bullet that gets you out of trouble. Like all fungicides, they only slow the rate of disease development. Their best place seems to be as a tank mix with another compatible chemistry.

Now for the 100 mph fast ball – fungicide resistance. Over the past 3 years we have been developing tools to assess mildew resistance to FRAC 11 and FRAC 3 chemistries. Last year with funding from AVF and Washington winegrape growers and the help of Michelle Moyer, Monica Cooper, Rhonda Smith, Mark Battany, Larry Bettiga, Glenn McGourty and crop consultants, we conducted an extensive survey for FRAC 11 resistance in Oregon, Washington, and California vineyards having trouble managing mildew. The results were not encouraging – over 90% of the 645 samples had the G143A mutation associated with strobilurin resistance. Based on the DMI bioassay results, it appears that most isolates are resistant to either FRAC 11 or FRAC 3 chemistries, with ~60% resistant to both.

The sky is not falling. We – there is a large team – do not know that these numbers represent the whole industry. The samples that we have examined are largely from vineyards that were having issues with managing mildew. This coming year, we are hoping to partner with even more grower groups and consultants to extend the survey for fungicide resistance. Our collaborator, Ioannis Stergiopoulos at UC Davis is busy sequencing samples looking for the potential of resistance to the FRAC 7 SDHI and FRAC 13 chemistries. Another collaborator, Tim Miles, now with University of Michigan, is working on developing new monitoring assays and improving existing ones. Lastly, with leadership of Brian Bailey at UC Davis, we are working on a computer simulation environment to test how fungicide programs effect disease spread and fungicide resistance development. This environment would similar to how engineer design and test structures in computers before building one or two prototypes to confirm simulations.

Now this leads to the last subject. Do you talk with your neighbors about what chemistries they are using and share what and when you use them? If not, why? Mildew does not respect a fence line. It will flow back and forth and your problems are your neighbors and theirs are yours. How can you properly rotate chemistries if your neighbor is out of sync with you? I have seen spray records from adjacent vineyards where each grower had a very good fungicide rotation, until looking at them in aggregate, the mildew in the area had seen a FRAC 11 fungicide application for 9 weeks in row. So much for resistance management. Strike three.

This is why we are working with Michelle Moyer to develop FRAME networks. FRAME (Fungicide Resistance Assessment Mitigation and Extension networks) networks will create the tools and infrastructure for growers, consultants, manufactures and researchers to collaborate in developing fungicide stewardship programs. These networks can be at various scales from a few adjacent growers to entire valleys. Their intent is to aggregate individual data so that your own limited data can be leveraged to increase its value to you.

Powdery Mildew Tough Dot Fungicide Resistance Testing Kit

If you are concerned about fungicide resistance, free kits are available for sampling at the April 3rd, 2018, CD11 LODI PCA NETWORK BREAKFAST MEETING (open to everyone, click for details). You can also drop us an email walt.mahaffee@ars.usda.gov or contact your local grower organization or county extension agent for a kit. We have a rapid (2-3 days from receipt of a sample) molecular assay to test for FRAC 11 resistance. All other fungicides require time-consuming bioassays. Unfortunately, we have limited capacity to conduct bioassays and will only be able to examine a subset of samples sent to us. If sending samples, please provide spray records for 2016 and 2017 as well as 2018 with your sample. We will select which samples get processed in bioassays.

Have something interesting to say? Consider writing a guest blog article!

To subscribe to the Coffee Shop Blog, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “blog subscribe.”

To join the Lodi Growers email list, send an email to stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “grower email subscribe” or click on “join our email list” to the right.

To receive Lodi Grower news and event promotions by mail, send your contact information to stephanie@lodiwine.com or call 209.367.4727.

For more information on the wines of Lodi, visit the Lodi Winegrape Commission’s consumer website, lodiwine.com.

To join the LODI RULES Sustainable Winegrowing Community as a grower or a vintner, email stephanie@lodiwine.com with the subject “LODI RULES.”