Vineyard management practices that improve fruit quality are only economically viable if the fruit price is high enough to offset increased costs to growers. For example, cluster thinning can help growers avoid delays in ripening and improve fruit quality, but it reduces the amount of harvestable fruit. For a grower to consider cluster thinning as a management tool, the loss in income from lower overall yields and increased labor costs must be compensated by a sufficient increase in the fruit price. Our goal was to develop a tool to help vineyard managers maximize profits by calculating their ideal level of cluster thinning, given the conditions of the marketplace.

Vineyard management practices that improve fruit quality are only economically viable if the fruit price is high enough to offset increased costs to growers. For example, cluster thinning can help growers avoid delays in ripening and improve fruit quality, but it reduces the amount of harvestable fruit. For a grower to consider cluster thinning as a management tool, the loss in income from lower overall yields and increased labor costs must be compensated by a sufficient increase in the fruit price. Our goal was to develop a tool to help vineyard managers maximize profits by calculating their ideal level of cluster thinning, given the conditions of the marketplace.

This article was originally published as a Cornell University Viticulture and Enology Program report, and is the work of Trent Preszler, Justine Vanden Heuvel, and Todd Schmit. A more comprehensive version of this article was punished in the May 2014 edition of Wines & Vines (“Cluster Thinning in Late-Harvest Riesling: Does it Pay?”, page 90-97). See the references section below for links to this and other related articles.

Leaves were pulled in order to photograph cluster thinning to one cluster per shoot (left) and two-plus clusters per shoot (right). No leaf pulling occurred on the actual vines studied. Copyright © Wines & Vines

Experimental design

A mathematical model was constructed that took into account the costs associated with labor and materials and the revenue from grape sales. We assumed stable production costs for labor, materials, chemicals, fuel, and maintenance. In addition, we assumed (1) the sale price of grapes is determined by both canopy management and market conditions, and (2) the market has a multi-tiered system for pricing grapes based on canopy management and quality, i.e., that buyers are willing to pay more for added value. From these inputs we have developed a simple tool (available in an Excel spreadsheet from the authors) which allows grape growers to calculate the minimum price per ton that would be necessary to adopt a particular level of cluster thinning. In addition, grower can calculate the optimum level of cluster thinning, based on yield, quality and buyers’ willingess to pay more for higher quality grapes. For details on the mathematical model and the equations, please see the original paper.

Results: A Finger Lakes Riesling example.

To illustrate the calculations, here is a case study using data for Riesling grown in the Finger Lakes. The values we used for the case study are shown in Table 1.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Table 1.Values used in Finger Lakes Riesling example.

| Variable Yield without cluster thinning Price without cluster thinning Production costs without cluster thinning Average number of clusters per shoot Fixed costs for cluster thinning Variable costs for cluster thinning Yield compensation in remaining clusters |

Estimate 4.3 Tons/Acre $1,200/Ton $2,400/Acre 3.25 $150/Acre $25/Acre 5% |

__________________________________________________________________________________

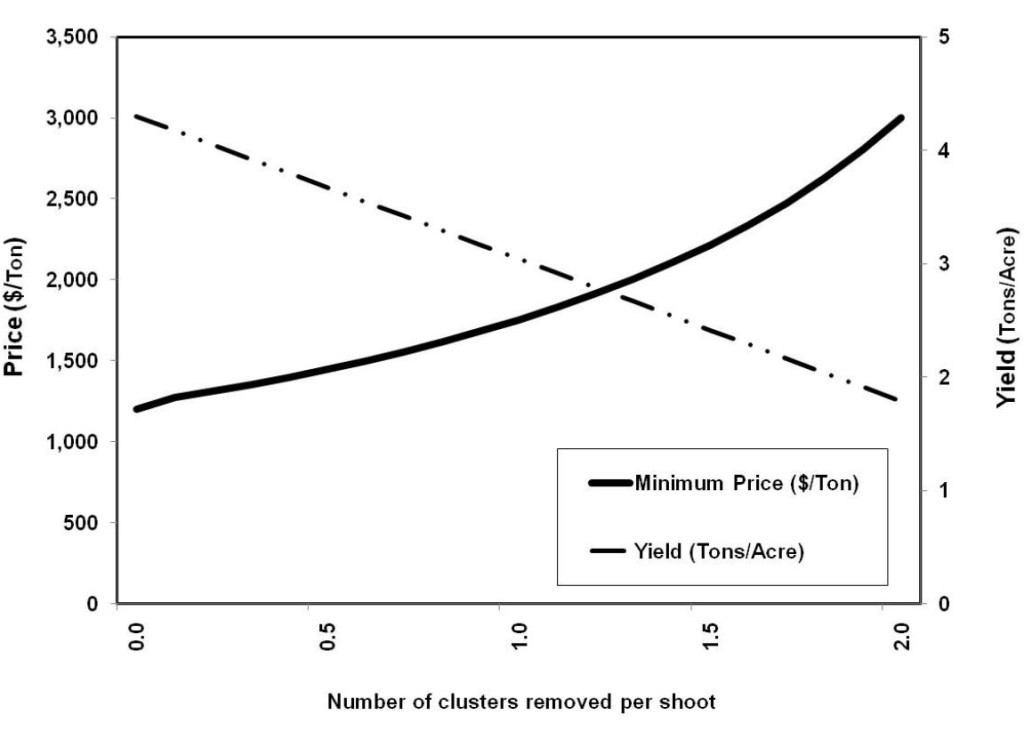

These calculations identify a threshold price for economic viability for each level of cluster thinning (Figure 1). In our example, for a grower to remove one cluster per shoot, a minimum price of $1,933/ton (or $5,335/acre) would be required.

If information on the expected increase in price for grapes produced through cluster thinning is available (when higher prices are paid for higher quality grapes), the most profitable level of cluster thinning can also be calculated. For this case study, the optimal level of cluster thinning is 0.73 clusters/shoot, based on higher production costs for cluster thinning, lost revenue from thinned clusters, and higher grape prices for increased fruit quality. These analytical tools can also be used for other grape cultivars and can be adopted to study the cost effectiveness of other viticultural practices.

Conclusions

- Using our new tools, vineyard managers can determine the increase in price-per-ton necessary to offset the costs of viticultural practices such as cluster thinning.

- They can also determine the optimal yield in a market which pays for added value for quality.

- An informed decision-making framework for crop load management will strengthen economic sustainability of wineries.

The bottom line

Our model can be used to assist vineyard managers in making decisions about the use of cluster thinning through analysis of expected costs and prices. A spreadsheet to assist with calculations is available by request from Justine Vanden Heuvel (jev32@cornell.edu).

Further Reading

- “Cluster Thinning in Late Harvest Riesling”, Wines & Vines.

- “A Model to Establish Economically Sustainable Cluster-Thinning Practices”, American Journal of Enology and Viticulture.

- “Cluster Thinning Reduces the Economic Sustainability of Riesling Production”, American Journal of Enology and Viticulture.